Introduction

Although Syria can trace its mass media development back to the publication of Hadikat al-Akhbar in Beirut in 1858, at a time when the future Lebanese capital was part of Ottoman Syria, printed publications within its modern-day borders began with the establishment of a printing press in Damascus in the 1890s.

The censorship policies of Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid II stifled the early growth of journalism and it was not until 1908 when the region was granted limited self-governing powers, that newspapers and publications began to expand significantly. This period saw the emergence of a relatively open and inclusive media environment, including the publication of al-Arous, the Middle East’s first magazine devoted to women’s rights, in 1910.

The Ottomans enacted greater control over the media during World War I but the press continued to prosper. By the time of the French Mandate, imposed across Syria in 1920, there were over 20 newspapers and 30 magazines in circulation. However, the French authorities ensured that Syrian press outlets only published content that took a favourable view of their policies. The French also introduced radio broadcasting to the region in 1938, with a station that serviced both modern-day Syria and Beirut, although it went on to become Radio Lebanon after the end of French colonial rule in 1946.

After independence in 1946, Syria created its own state-run radio broadcasting organization and was on air for nine hours per day by 1950. The country’s print media environment also boasted many newspapers and almost all were affiliated with a particular political party or interest group. With the rise of Arab nationalism, and Syria’s merger with Egypt to form the United Arab Republic (UAR) in 1958, all political parties and affiliated newspapers were banned. In 1960, television broadcasts began in Syria, the same day as in Egypt, although initially poor infrastructure and the wars with Israel in 1967 and 1973 meant that television broadcasting essentially stagnated for 15 years.

Syria withdrew from the UAR in 1961, but the previous, politically vibrant print media environment did not return. The Baath Party came to power in 1963 and the same year introduced the Emergency Law that put the government in control of all media. Every independent newspaper was outlawed, and the entire media apparatus was effectively rendered a government mouthpiece by the time Hafez al-Assad became president in 1970. Only state-sponsored media outlets were permitted to operate, consisting of a national television station, a radio station and three national newspapers.

Satellite television was introduced in 1995, which challenged the government’s monopoly over information, followed by the internet in 1998, although access was restricted and heavily monitored. Hafez al-Assad died in 2000 and was succeeded as president by his son Bashar, who initially raised hope of a more open media environment by permitting private publications.

However, the government’s rewarding of favourable coverage, in conjunction with the 2001 Press Law allowing the state to suspend publications deemed to be violating regulations, ensured the continuation of a compliant press. Private television and radio stations were officially permitted in 2005, but they could not broadcast news coverage and were only granted a license at the discretion of the government.

A key feature of this era of private media ownership in Syria was that licenses were generally awarded to the country’s prominent Alawite businessmen, with close ties to the al-Assad regime. Examples include Rami Makhlouf, a cousin of Bashar al-Assad and owner of al-Watan newspaper, and Majd Sulaiman, son of a prominent security advisor in the Hafez al-Assad era and owner of the self-proclaimed “independent” Baladna newspaper.

The growth of social media and citizen journalism afforded Syrians some degree of freedom of expression, and these new platforms played a significant role in conveying information during the 2011 uprising against the al-Assad government.

The ensuing civil war has nullified government media regulation in many areas, and dozens of private outlets have materialized. However, the ongoing conflict means that journalists operate in a deadly environment of violence and intimidation.

Freedom of Expression

The current conditions in Syria mean it is one of the most dangerous places in the world for journalists, ranking 177th out of 180 countries in Reporters Without Borders’ 2016 World Press Freedom Index.

Following the 2011 uprising, the Syrian government enacted a series of legislative measures to improve media freedom and appease the populace. A 2011 law banned media monopolies and outlawed the ‘arrest, questioning or searching of journalists’. The redrafted Syrian constitution, approved in 2012, guarantees ‘freedom of the press, printing and publishing, the media and its independence in accordance with the law’. However, these provisions have been undermined by the government’s existing legislation and new initiatives designed to suppress opposition. One such example is the 2012 Antiterrorism Law, which allows journalists to be arrested and detained under the vague charge of ‘publicizing terrorist acts’.

Many Syrian journalists have been detained, and continue to be held, by the Syrian government since 2011. In 2012, Ali Mahmoud Othman, a citizen journalist who ran an amateur media centre based in Homs, was arrested by government authorities. His whereabouts are still unknown. In 2013, Mazen Darwish and four colleagues from the Syrian Centre for Media Freedom and Expression were arrested for publicizing terrorist acts. Darwish was finally released in August 2015.

As of December 2016, at least seven journalists remain in government custody. Bashar al-Assad has also pursued journalists working for pro-government outlets if they are considered to be overly critical or outspoken. In August 2016, Musaab al-Awdat Allah, writing for the government-owned Tishreen newspaper, was killed by government affiliates in Damascus for failing to adhere to the state version of current events.

In areas outside government control, regional militias operate with their own media networks, predominantly on social media, and journalists working in these regions are also subject to violence and intimidation. In 2014, media activist Ahmad al-Masalmeh was shot dead by unidentified gunmen in Daraa, while Islamist group Jaish al-Islam arrested citizen journalist Anas al-Khouli in 2015, following his coverage of protests against the group.

In areas under the control of the Islamic State (ISIS), journalists have been forced to swear allegiance to the terrorist group and subject themselves to its censorship. In Raqqa, ISIS’ de facto capital, a group of citizen journalists has established the reporting collective Raqqa Is Being Slaughtered Silently (RBSS) to convey the reality of life under ISIS rule.

However, journalists suspected of being part of the network are pursued and punished brutally. In July 2015, two men believed by their captors to be RBSS reporters appeared in an ISIS propaganda video before being executed. In October 2015, two RBSS journalists, Ibrahim Abd al-Qader and Fares Hamadi, were murdered by ISIS operatives in Urfa, Turkey. Since 2014, ISIS has also executed a number of foreign journalists in Syria, including Americans James Foley and Steven Sotloff, and Kenji Goto from Japan.

Besides working under the various restrictive regulations of state or non-state authorities, journalists in Syria also face the deadly task of covering the conflict. In 2016, the Committee to Protect Journalists ranked Syria as the ‘most deadly country for journalists’ for the fifth year running. Although the number killed (14) in 2016 represent a decline from the record levels of recent years, 107 journalists are believed to have died in the country since the conflict began in 2011.

In Syria’s Kurdish region, the de facto autonomous Rojava, media freedoms are enshrined in its own 2014 constitution and initiatives such as the 2013 Union of Free Media, established to oversee and protect the region’s press. However, the Rojava constitution stipulates that freedom of expression cannot come at the expense of the region’s security and autonomy, while the influential Democratic Union Party (PYD) dominates media regulation.

Television

Television is widely considered to be the most important source of news in Syria. Pan-Arab outlets such as al-Arabiya, al-Jazeera and al-Mayadeen are popular among viewers in both government-controlled and rebel areas, as well as international news outlets such as the BBC. The most significant Syrian channels are as follows:

Orient TV – Syrian opposition satellite channel owned by businessman Ghassan Aboud. It was first established in Damascus after being granted a license in 2009. However, the channel’s critical stance quickly riled the government and it was raided by security forces later in the year. Employees were forced to sign agreements not to work for the channel, which subsequently moved to Dubai. The channel played a prominent role in documenting the 2011 uprising against the al-Assad government, often featuring amateur footage submitted by citizens and activists. Orient TV is currently the most popular anti-government channel, although critics have highlighted the Sunni bias and sectarian tone in some of its programming.

Free Syrian Army TV – Rebel-affiliated channel that broadcasts primarily on YouTube, often documenting Free Syrian Army (FSA) military activities.

| Channel | Percentage of respondents who view channel most in government-controlled areas | Percentage of respondents who view channel most in contested/anti-government areas |

| Al-Arabiya (Saudi) | 12.8% | 25.4% |

| Al-Jazeera (Qatari) | 7.4% | 13.2% |

| Orient TV | 1% | 10% |

| Sama TV | 24.4% | 3.8% |

| Al-Jadeed TV (Lebanese) | 6.4% | 0.6% |

| Al-Mayadeen (Lebanese) | 12.8% | 5.6% |

| BBC (British) | 5.1% | 9.7% |

| Al-Ikhbariya Syria | 8.7% | 2.8% |

| Sky News Arabia (British) | 1.9% | 8.8% |

Table 1. Most popular television channels by percentage of respondents who view it. Source: Media in Cooperation & Transition August 2014 Survey.

Sama TV – Private channel based in Damascus with close links to the government. It was launched in 2012 and airs a variety of talk shows and current affairs programmes. The channel has recently acquired a reputation for airing gruesome images of atrocities purportedly committed by rebel groups.

Al-Ikhbariya Syria – Pro-government news channel established in 2010. In 2012, rebel gunmen attacked the channel’s offices near Damascus, killing several employees. Al-Ikhbariya serves as the government’s primary news outlet, with President al-Assad providing a rare televised interview with the channel in 2013.

Syria Satellite TV (RTV) – State-owned satellite station launched in 1995 from Damascus. The channel serves as a government mouthpiece and has been particularly critical of the Gulf states since the 2011 uprising. In response, Gulf states acting as part of the Arab League have lobbied for the channel to be removed from major Arab satellite networks.

Aleppo Today – Rebel-affiliated television channel that originally broadcast from Aleppo but relocated to a location outside Syria in 2012 following government pressure. The news channel broadcasts still images for 24 hours per day and sources information and footage from a network of contacts inside Syria. The channel is funded by an anonymous group of Syrian businessmen.

Radio

Radio is a popular news medium in Syria and has grown in significance since the start of the current conflict. Radio stations are cheaper to establish and maintain compared to television channels. As of May 2015, there were at least 17 stations transmitting across Syria, although the majority broadcast from outside of the country for security reasons. Some of the most notable stations are as follows:

Radio Damascus – State-owned radio station that dates back to 1947. It currently serves as the main pro-government radio news source. In December 2011, Radio Damascus host Shukri Abu al-Burghul was shot dead by unidentified gunmen.

Rozana – Independent station financed by French media support organization Canal France International. The station originally consisted of five Syrian broadcast journalists, including three defectors from state media, and over 30 correspondents spread across Syria. In late 2014, the station’s broadcasting equipment was temporarily seized by the al-Nusra Front, then affiliated with al-Qaeda.

Radio Alwan – Established by a university student in 2013 and originally with offices in Idlib and Aleppo. The station currently broadcasts news and current affairs programming from Turkey, with a network of correspondents and citizen journalists within Syria.

Radio al-Kul – Primarily news-focused station linked to the Syrian National Coalition. Radio al-Kul also broadcasts daily religious programming designed to ‘deconstruct’ extremist Islamist ideologies and influence listeners who are vulnerable to radicalization. It currently broadcasts from Istanbul.

Press

The Syrian newspaper environment remains dominated by pro-government publications, mainly due to the infrastructure required to maintain a press outlet. A few opposition publications have emerged since the 2011 uprising, but meaningful circulation is hindered by the ongoing civil war. The most notable Syrian newspapers are as follows:

The Syrian government currently operates three newspapers. Al-Baath, founded in 1948, is the official publication of the Syrian Baath Party. This has since been joined by al-Thawra, established in 1963, and Tishreen in 1975. Traditionally, all three publications have focused on the activities of the president and the government. Tishreen was the most popular prior to the 2011 uprising, with an estimated daily circulation of 50,000 in 2004.

Also prior to 2011, independent newspapers were owned almost exclusively by businessmen with close ties to the al-Assad government. Rami Makhlouf’s al-Watan was established as a privately owned publication with a distinct pro-government slant. The newspaper dedicated a full page of its print issue to denouncing the actions of the anti-al-Assad March 14 Alliance in Lebanon.

Opposition newspapers in physical form are restricted to local circulation, but several have emerged in recent years. In 2011, Enab Baladi was established by activists as an opposition weekly publication based in Daraya. Although it has since been forced to operate as an ‘underground newspaper’, the publication has overcome hostile conditions to grow into an online Arabic- and English-language news source.

This has prompted a digital conflict between pro-government users and rebels, who have both mass reported Facebook pages affiliated to a certain side on the grounds that they violate user rules, leading to Facebook to remove the reported pages.

The pro-government Syrian Electronic Army (SEA) monitors social media accounts, particularly on Facebook, and targets anti-government sentiments by mass spamming or real-life intimidation of users.

Online Publications

The Syrian government extensively censors the internet in areas under its control to filter out opposition coverage. This censorship has increased since the start of the conflict. Furthermore, the government actively targets anti-government websites operating in Syria, such as the Hadath Media Centre, established in 2013 in Aleppo as a repository for photos and videos of the conflict, and bombed by al-Assad’s forces in 2015. Yet activist groups have managed covertly to establish and maintain several websites outside of government control. Deir Ez-Zor 24 was founded in 2014 by civilian journalists seeking to document atrocities purportedly committed by the Syrian government and ISIS. RBSS was also established in 2014 as an underground operation to report on Raqqa under ISIS control.

Other online publications are based outside of Syria, and therefore outside of government censorship, and rely on communication with sources inside the country. Baladi was established in 2015 by the Union of Syrians Abroad to serve as a news network for reporting and documenting the conflict inside the country. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, founded in 2006, is a UK-based organization that reports on the conflict via a sizeable network of Syrian-based sources and correspondents.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Media’ and ‘Syria’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website:

Social Media

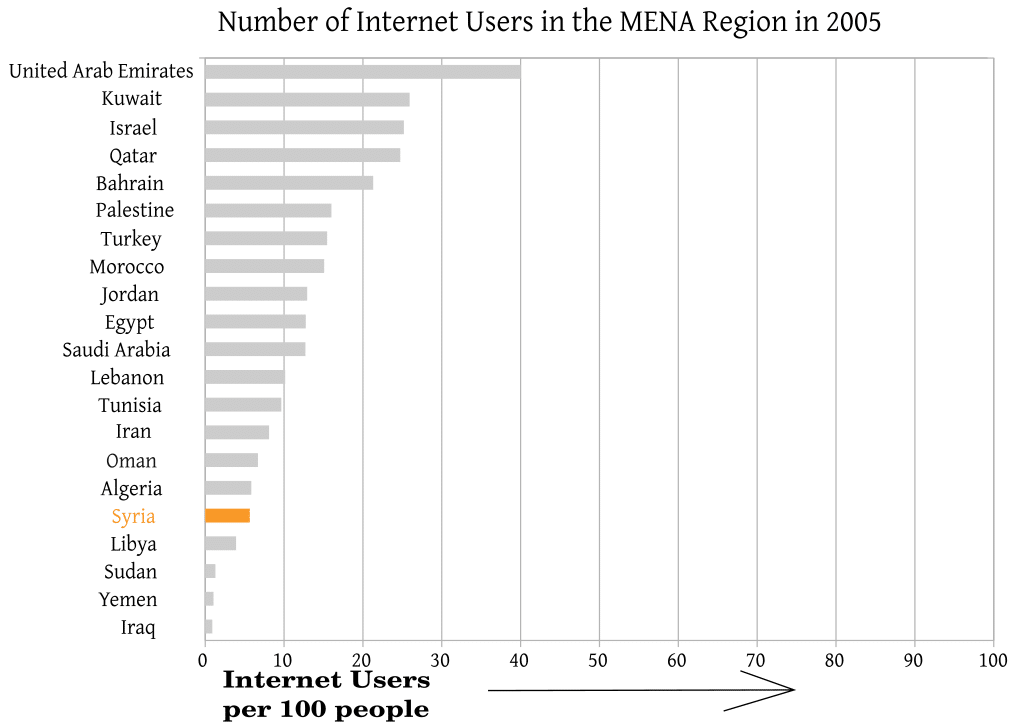

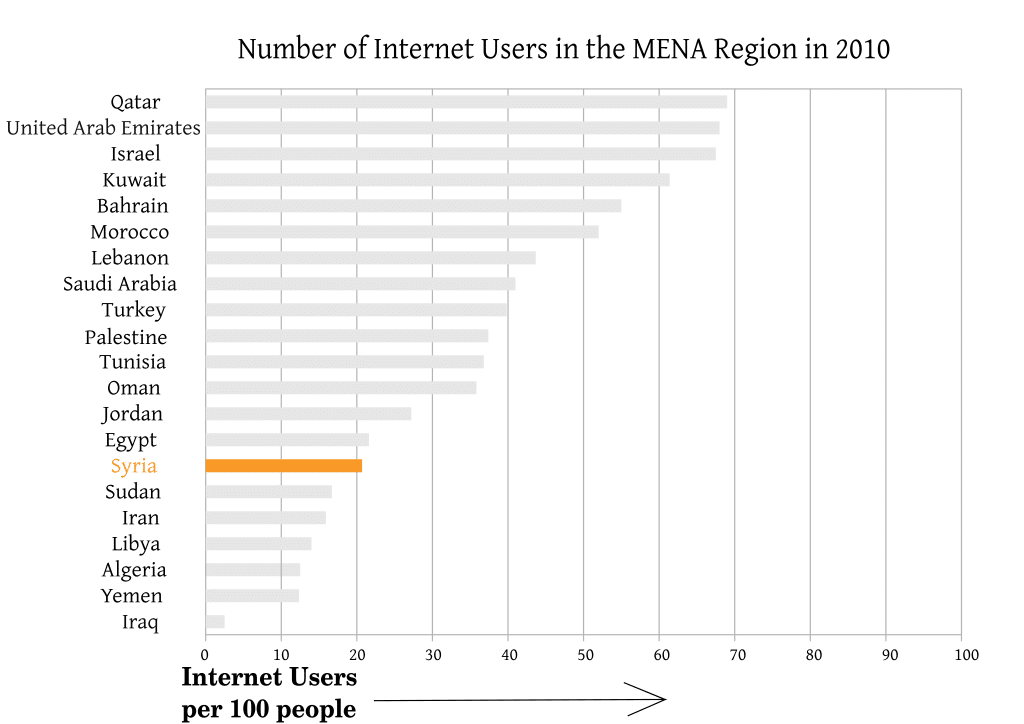

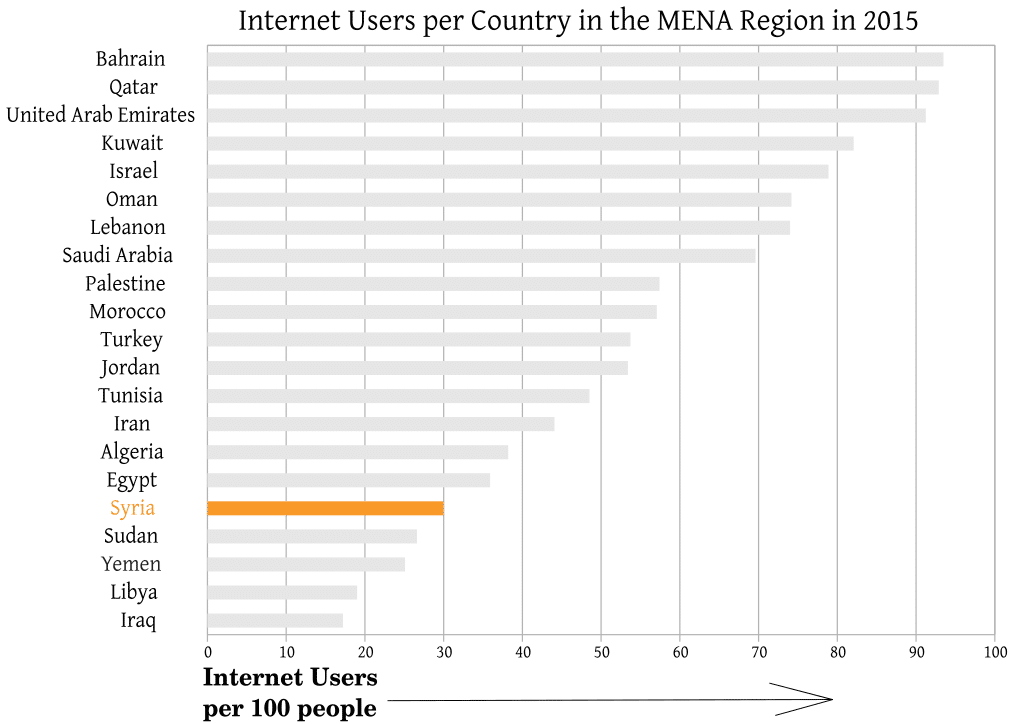

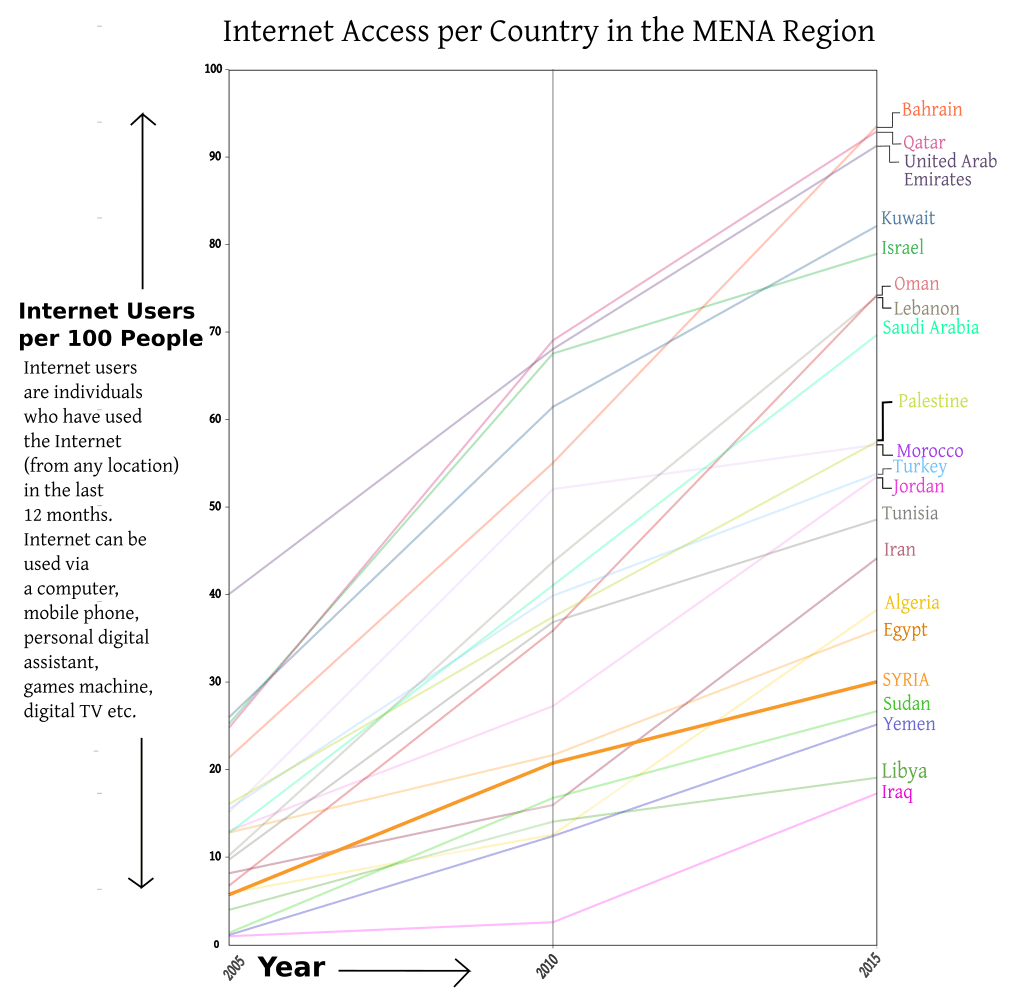

Syria’s internet penetration is poor by regional standards and has been both damaged and manipulated by parties to the conflict. Nevertheless, social media remains a vital tool for citizens to keep in touch and convey the reality of their living conditions. Meanwhile, state and non-state organizations are also active on online platforms to promote their causes, and Syrian authorities regularly monitor social media to keep track of opposition activity.

Facebook is by far the most popular social network in Syria and has been ever since the government lifted a four-year ban on it in 2011. All major militias operating in the country have a Facebook page and ordinary citizens use the website, along with YouTube, to post footage and their version of events unfolding in the country.

Table 2. Most popular social media platforms in Syria by percentage of respondents who use them. Source: Media in Cooperation & Transition August 2014 Survey