Political parties, including the opposition, were free to operate at times, while at other times, they were suppressed.

Introduction

Syria’s political nature changed throughout history. Political parties, including the opposition, were free to operate at times, while at other times, they were suppressed. The increasing political role of the army was one of the most vital factors in this process. It attempted to impose restrictions on free political participation and repeatedly tried to hold onto power. Eventually, power and authority were monopolised during Hafez al-Assad’s reign, when the military and security apparatus became the regime’s spine. This regime has survived even after the start of the 2011 revolution.

In this article, Fanack will address how political parties’ role has diminished in Syria and how this role was eventually abolished.

The Mandate and the Independence

The Syrian opposition had been present in the Syrian parliament since the French Mandate. Among the Syrian MPs were those who fundamentally rejected signing any treaties with France and demanded their departure from the Syrian lands without any conditions. Also, some opposed the policies of the consecutive governments formed during the occupation from the 1920s to the 1940s. In other words, even during the Mandate, several blocs, including the opposition, were present in the Syrian parliament. For instance, the Arab Socialist Party, one of the two main blocs comprising the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party that has been ruling Syria for over 50 years, was an opposition bloc in the parliament before independence.

Political life in Syria revived after independence in 1946. Syrian parties from different affiliations and ideologies started mobilising their supporters to guarantee as many parliamentary seats as possible and to gain a stronger position. Law no. 325, issued in 1947, amended the elections law, making them free and direct. Following that law, free elections took place in Syria, in which all political blocs competed.

After the Nakba and the establishment of Israel in 1948, Syria was engulfed in chaos due to public anger and unrelenting protests defending Palestine. Political parties, the government, and the army blamed each other for the Nakba. The American-Soviet conflict over control in the Arab countries, including Syria, also had its share in escalating the chaos because Syrian parties back then either supported the west or the Soviets, which led to divisions within the country.

Military Coups

The Syrian army inherited the armed forces from the Mandate. It was one of the army’s most vital pillars and was at odds with the ruling political class. The armed forces exploited the frequent mass protests in late 1948 and early 1949, which forced the Syrian government to resign. In March 1949, they mounted a coup led by an officer called Husni al-Za’im, and declared military rule. They abolished the political process, which was Syria’s most defining feature after independence.

Following these developments, the scene was bleak at the time. Some politicians were enticed to form civilian governments that reported almost directly to the military.

However, the second coup led by general Sami al-Hinnawi in August 1949 somehow brought back political life, allowing parties to resume their work, excluding the Communist party. Additionally, the army was prevented from interfering in politics. In the parliamentary elections of November 1949, the People’s Party, one of the most prominent Syrian parties in that period, amassed most of the parliamentary seats. The Ba’ath Party, the Muslim Brotherhood and other political blocs shared the remaining seats, while the National Party boycotted the elections.

Soon, a third coup led by general Adib Shishakli took place in December 1949 and overthrew al-Hinnawi’s government. Political freedom was partly preserved. During Shishakli’s reign, there was a struggle between the government and parliament and a parliamentary struggle between secularism and the role of Islam in the state. Some left-wing blocs called for secularism, which conservative currents totally rejected. The latter triumphed by constitutionally preserving the state’s and the president’s Islamic character. But things changed during the same period when a new constitution was drafted for Syria in 1950, in which the phrase “Islam is the official religion of the state” was removed. Also, any reference to Syrians’ religion was removed from their IDs.

Suppressing the Opposition

The coup leaders’ authority weakened compared to the politicians’, especially with the increasing influence of the People’s Party and its endeavour to form a new government without taking Shishakli’s demands (to grant the army a greater political role) into account. On the other hand, the crisis between parties in the parliament escalated, especially due to the conflict between feudal lords and peasants.

This led to a new coup led by Shishakli that overthrew the president and the government in November 1951. Shishakli also dissolved the parliament and political parties, including his ally, the Ba’ath Party. Then he founded the Arab Liberation Movement, the only legal party in Syria until 1954. All those who opposed the coup leaders were arrested, starting with party leaders. Later, Shishakli backed down, fearing the mass that began to rally against him.

The political parties, even rival ones, found each other in their campaign against Shishakli. The People’s Party, the National Party, the Ba’ath Party, and the Communist Party were united in opposition against his regime. Protestors filled the streets in various cities, trying to overthrow the Shishakli regime. However, a movement in the army began to turn against him in support of popular opposition. Eventually, Shishakli fled Syria in 1954, and politics returned to what it was before the coups.

All coups impacted political life in Syria, either by abolishing, undermining or indirectly affecting it. In addition, all of them strengthened the army, increased its budget and headcount, and enhanced its leadership position in the ruling party, which would significantly affect politics and history of Syria.

The Golden Era

Historians believe Syria’s ‘golden era’ was between 1954 and 1958, when politics and press thrived. There were parliamentary elections as well, one of which was considered the fairest elections in Syria’s history. Leftist and nationalist forces advanced at the expense of the traditional parties.

After these elections, workers and peasants gained a strong representation in parliament. Each political party had parliamentary seats to utilise in pushing its national project. At that time, the Syrian political parties also adopted different perspectives regarding foreign affairs. Some favoured rapprochement with Iraq and Turkey, which were closer to the Western alliance, and some preferred a rapprochement with the Soviet Union.

Unity Overthrows Political Life

Nationalist and leftist forces in Syria converged with Egypt following the growing power of Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser. The Ba’ath Party’s orientation in Syria was clearly national. Unifying the Arab countries was its first objective, and among the political parties it was the strongest proponent of a unity with Egypt. At that time, the Ba’ath Party had a large popular base, many parliamentary seats, and the capacity to influence other political forces.

The union was declared in February 1958, and Syria became the northern region of the United Arab Republic, led by Nasser. The Ba’ath Party postponed discussing the form of the union until it was established and embraced dissolving itself, aborting its leading role and paving a path for an autocratic rule.

Nasser abrogated political life in Syria and banned parties. Syria began to be governed by his military and intelligence services. Even leaders of the dissolved Syrian parties were prevented from practising politics under the law Nasser had issued on March 12, 1958. Another law followed, establishing supreme state security courts, known later as a dictatorial authority capable of deciding on various organisational, political and social matters.

Nasser nationalised factories and companies and issued the Land Reform law, which was categorically rejected by landowners, capitalists, and the leaders of the dissolved bourgeois traditional parties. In addition, the security and intelligence services seemed to frustrate even the nationalist political forces that strongly favoured unity. In other words, a general feeling spread in the country, rejecting Nasser’s dictatorship in Syria. A stance against unity began to bring together various political forces in the form of covert opposition to Nasser.

A rift began to appear amid the security services between its Egyptian administration and its Syrian officers. It escalated into a conflict between Field Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer, the United Arab Republic army commander, and Abdel Hamid al-Sarraj, Minister of Interior and head of the Executive Office of the Northern Region. In other words, confusion within the security apparatus began to surface.

On September 28, 1961, the Syrian army declared a unilateral separation from Egypt, with the support of the dissolved parties headed by the Ba’ath party. At the time, their leaders signed the separation statement indicating that the main problem was Nasser’s authoritarianism and abolishing political life in Syria.

Separation

Separatists from the army took control, led by Abd al-Karim al-Nahlawi, the de facto military commander of the separation. He imposed his authority over the country. Parliamentary elections were held, allowing parties to be democratically represented. However, despite allowing them to form a government, actual authority remained in the army’s hands via the National Security Council that al-Nahlawi established after the separation.

Some members of the Syrian parliament embarked on an opposition campaign against the state structure and the power granted to the military, calling for an end to the army’s dominance over politics. The campaign prompted the government to resign. In addition, the army turned against the change and restored its control over the country. It started arresting politicians and parliamentarians. Consequently, the army faced widespread protests in the Syrian streets, especially in Aleppo.

Political chaos, divisions among the parties and the struggle between politicians and the army continued until a group of Ba’athist officers staged a coup on March 8, 1963. They were members of the so-called “Military Committee” formed in Egypt during the period of unity, among them Hafez al-Assad. The coup was approved by some Ba’athist leaders and rejected by others. Nevertheless, this date was the beginning of absolute Ba’athist rule in Syria.

The Ba’ath State

Between 1963 and 1970, the country lived through a military-political conflict, especially between the political poles of the Ba’ath Party and the Ba’athist military leaders, and even among the members of the same military committee that staged the 1963 coup.

Political life during that period regressed in favour of the growing military power. The party, which was once a democratic entity and influential through parliament, had become represented by competing military generals. The disputes eventually led to two major coups, the first of which was led by Salah Jadid on February 23, 1966, against the Ba’athist President of the Republic, Amin al-Hafez. Hafez al-Assad led the second on November 16, 1970, against the party’s regional leadership, its leader Salah Jadid, and other Ba’athist leaders. The two coups removed all of Assad’s rivals. In this way he monopolised power over Syria.

Assad’s Syria

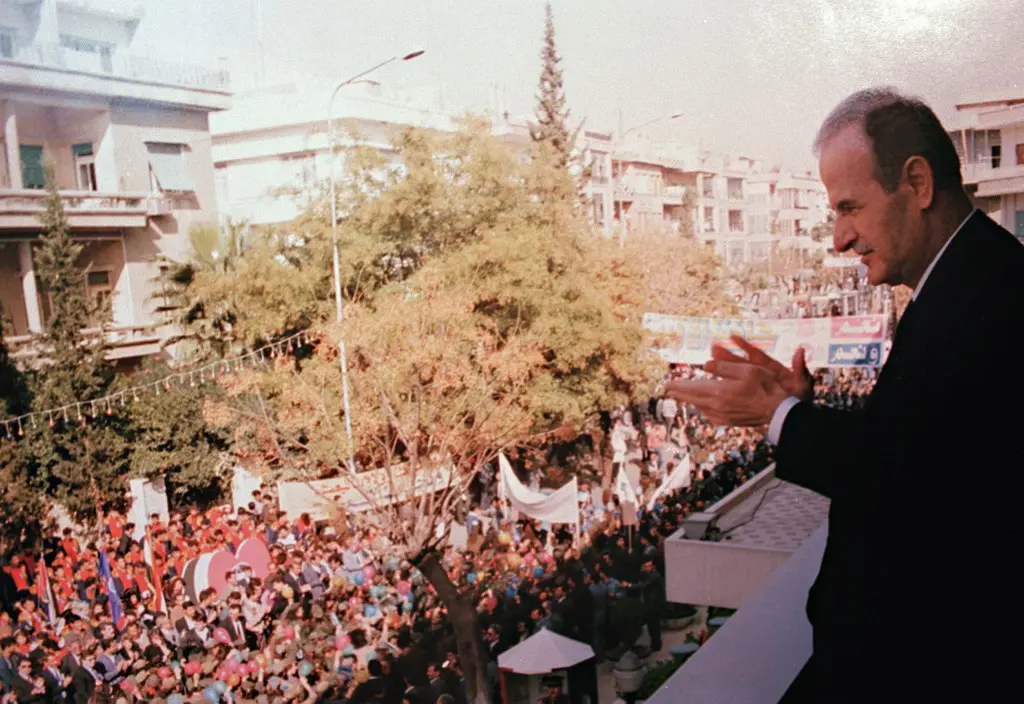

As soon as Hafez al-Assad assumed power, he removed his opponents and prevented partisan political action. He gathered the parties loyal to him within the National Progressive Front. The latter incorporated the Ba’ath Party, the Communist Party, the Socialist Union Party, and the rest of the blocs that supported the Assad coup. Then, syndicates and federations, which followed the Ba’ath Party’s leadership, were established. By doing this, Assad resisted any popular movement against his rule.

He also secured foreign support through his rapprochement with the Soviet Union and Iran, after the Islamic Revolution. He maintained good relations with some Arab countries to ensure Arab support.

In Syria, he won over the clans of the eastern region as well as some Kurdish groups. He secured the loyalty of the Alawite sect from which he descended and bolstered its presence in the army and the security apparatus. Thus, he established security branches in various cities and villages to lay the foundations for a dictatorial rule that would be able to stay on while suppressing any opposition.

During his rule, Assad did not face any opposition except for the Muslim Brotherhood, an active party in Syrian politics before the Ba’ath came to power. The Muslim Brotherhood sometimes won parliamentary seats and, at other times, boycotted the elections. They practised politics like any other bloc within the Syrian political structure, before it was suppressed shortly after the Ba’ath party took power.

In 1979, a dissident group within the Muslim Brotherhood called the “Fighting Vanguard” emerged and endorsed an armed struggle against the Syrian regime, killing a group of student officers from the Alawite sect at the Artillery School in Aleppo. Therefore, Assad outlawed the group and threatened with execution anyone who joined it.

Syria witnessed intermittent military confrontations between the army and the Fighting Vanguard. But the decisive point was the army’s siege of Hama and its massacre in 1982, when more than 10,000 citizens were killed, according to the various historical references that documented the massacre. It meant the end of any movement opposing the Assad regime, giving Assad greater control over all aspects of life in the country until he died in 2000.

Damascus Spring

After Hafez al-Assad passed away, a group of Syrian thinkers and writers with oppositional tendencies gathered to present a set of demands. It aimed to restore and legalise free political participation, establish free media, end the state of emergency, and allow partisan pluralism. This movement was called the “Damascus Spring“.

Initially, these demands were not suppressed, especially since they did not reject Bashar al-Assad as the new president. Subsequently, political forums were held, but this situation did not last long. Once again, the regime, now under Assad junior, suppressed these movements, arrested their leaders and imprisoned them on charges of violating the constitution.

Syria quickly returned to its former state as a country ruled by a dictatorial regime devoid of any actual opposition. The situation continued even after the outbreak of the revolution against the Assad regime in March 2011. At that time, the opposition movement took various forms, civil and military, leading to an open war between several parties. After that, Syria was devastated, split into territories controlled by different powers, each relying on foreign support. And despite all of this, Bashar al-Assad remained the country’s president.