Introduction

Syria is not a major global energy player when compared with energy giant Iraq, with whom it shares a long border to the east. However, it is the largest producer among its eastern Mediterranean neighbours, which include Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey and Israel.

Once part of the Ottoman Empire and then a French protectorate, Syria gained its independence in 1946. Upheaval dominated Syrian politics from independence until the late 1960s. The country briefly merged with Egypt before the merger was annulled in 1961, an indicator of the instability that culminated in the 1963 Baathist coup.

A series of events following defeat in the 1967 Six-Day War with Israel saw Defence Minister Hafez al-Assad assume control of the country in a bloodless 1970 interparty coup. He subsequently instituted effective one-man rule. Hafez’s son, Bashar al-Assad, has ruled Syria since his father’s death in 2000. In 2011, following anti-government uprisings, the nominal republic descended into civil war.

The splintering of Syria into numerous spheres of control, with the al-Assad government controlling territory predominantly in the south-west of the country, has had a dramatic impact on Syria’s energy sector. Damage to energy infrastructure has adversely affected production, revenues, domestic consumption and investment. Furthermore, the disintegration of the state has important implications for the energy sectors of its neighbours, especially Iraq and key transport country Turkey.

Oil and Gas

Syria’s conventional [1] crude oil reserves have been estimated at 2.5 billion barrels by Oil & Gas Journal and BP. Syria also has shale oil resources, with estimates of reserves as high as 50 billion tons as of late 2010, according to Syrian government sources. The Syrian government has indefinitely delayed a bidding round for the country’s shale resources, which was scheduled for November 2011, leaving any discussion of shale reserve production outside the scope of the present discussion.

At the 2009 conventional reserves-to-production ratio of 18.2 years, Syria maintains the second-smallest reserves-to-production ratio among the major oil producers in the region [2]. Nevertheless, Syria’s oil production, which averaged over 400,000 barrels per day (bbl/d) between 2008 and 2010, is relatively high for the entire MENA region taken together. Historical production has been declining since its peak in 1996, and with the onset of the civil war has declined dramatically, dipping significantly below consumption.

According to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), production hit its lowest level in more than 30 years reaching 25,000bbl/d in January 2014 – predominantly outside areas controlled by the Syrian government (more on this in Civil War: Dispersed Control of Oil Resources).

Much of Syria’s crude oil is heavy (low gravity) and sour (high sulphur content), making processing and refining difficult and expensive. The pre-war years saw an increased emphasis on the use of enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques to produce Syrian oil, with several companies planning additional investment in the country’s mature oilfields. This was viewed as a critical component of new production given the low likelihood of new finds.

Also prior to the war, oil exports had been a vital component of Syria’s export economy, accounting for roughly 35% of the country’s total export revenues in 2010, according to IHS reports. In the 12 months prior to the protests in March 2011, approximately 99% of Syria’s crude exports went to Europe (including Turkey), according to the EIA. With the introduction of sanctions by the United States, European Union and others, many of the international oil companies (privately held) and national oil companies (predominantly government held) doing business in Syria ceased operations, significantly limiting Syria’s exploration and production capabilities.

The only oil companies still operating in Syria as of September 2013 were Hayan Petroleum and Elba Petroleum Company. In December 2013, however, the Syrian government and Russian petroleum company SoyuzNefteGaz signed a 25-year offshore exploration agreement. The contract stipulates that the company will conduct surveying and exploration for oil and gas in the region extending from the southern shores of Tartous to the city of Banias.

This area is estimated at 70 kilometres in length with an average width of 30 kilometres, and comprises a total area of 2,190 square kilometres. The contract is for exploration, which is more viable in the present environment than production. If oil or gas is found, however, a complicated road would lie ahead for the regime and SoyuzNefteGaz.

With production at a virtual standstill, the lack of crude oil has led the country’s two major state-owned refineries in Homs and Banias to operate at roughly half their pre-conflict capacities. This has resulted in supply shortages of refined products including heating and fuel oil. The combined nameplate capacity of the two refineries at the end of 2013 was just below 240,000bbl/d, according to Oil & Gas Journal.

All refinery expansion or new construction plans are on hold due to the fighting. In 2012, Syria’s consumption of refined products fell below 260,000bbl/d, and EIA estimates that 2013 consumption will be even lower once the data become available. The Syrian government continues to subsidize domestic consumption of refined petroleum products in territories it still controls. In the first half of 2013, the government spent more than $1 billion on petroleum subsidies, according to the Minister of Petroleum and Mineral Resources.

Syria’s 2010 proven natural gas reserves have been estimated by Oil and Gas Journal at 8.5 trillion cubic feet. Prior to the conflict, more than half of Syria’s natural gas production came from non-associated fields, with those volumes being redirected to oilfields for reinjection and to domestic demand centres throughout the country’s now damaged domestic pipeline network. Production and consumption in 2012 were equal at 228 billion cubic feet, reflecting the collapse in import capacity.

In 2008, Syria became a net importer of natural gas. The only previous source of natural gas imports, the Arab Gas Pipeline, became the target of attacks as the conflict intensified, forcing the shut-down of the pipeline (see map 2). Production declines from available data suggest production losses upwards of 20%. Estimates from mid-2013 indicate that the losses from the hydrocarbons sector have topped $12 billion, from both direct causes (damage to infrastructure, spillage and theft) and indirect causes (lost exports). According to the Syrian government, damage to the country’s energy infrastructure and spilled or stolen oil and natural gas cost the country approximately $1 billion through the end of July 2013.

Civil War: Dispersed Control of Oil Resources

While oil production activities have decreased dramatically due to the fighting, some level of production has been maintained. This production is split between the various groups controlling pieces of Syria. The prominent armed groups are the predominantly Syrian al-Qaeda-affiliated al-Nusra Front, the transnational Muslim extremist organization Islamic State (IS) (or ISIS, formerly al-Qaeda in Iraq), the moderate rebels, the YPG (Syrian Kurds) and the Assad regime. For some, the rebellion is against al-Assad’s political repression whereas for others the turmoil has presented the opportunity to create a territory ruled by militant Islamic law.

IS, which was born from the struggle against American occupation of Iraq after 2003 and has found fertile ground in a fragmenting Syria, is the main proponent of the latter. As such, IS-controlled parts of Syria have become a magnet for radicalized Muslims around the world who wish to live in a proto-state governed according to extremist interpretations of Islam.

The violence stemming from IS constitutes a tangible threat to non-Muslims and Muslims adhering to other interpretations of Islam in Syria itself, in neighbouring territories such as Iraq (e.g. Yazidi and Christians) and further afield, including Western capitals, as has been communicated by the group’s leadership.

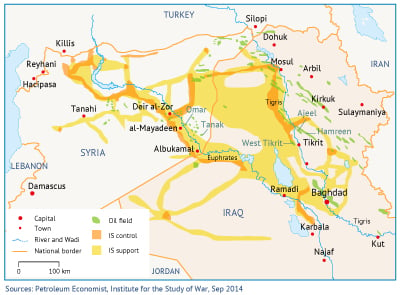

The expansionist and hyper-violent modes of behaviour displayed by IS have prompted detailed reviews of its ability to fund itself and raised concerns about the fate of Syria’s oil production. Most of Syria’s oil reserves are located in the east, near the border with Iraq and along the Euphrates River, with a number of smaller fields in the centre of the country. According to news reports in late 2013, the Syrian government has lost control of nearly all of the country’s major oilfields. Syrian Kurdistan (in yellow above) contains roughly 60% of Syria’s oil reserves. The remainder is controlled by IS.

Maplecroft, the risk management firm, estimates that IS now controls six out of ten of Syria’s major oilfields (and at least four fields in Iraq). Revenue streams associated with newly controlled production are aided by the long-standing networks of black-market oil sales in the Levant.

Figures from the EIA estimate IS oil production at 30,000bbl/d in Syria, implying earnings of $1.2 million per day when sold at the black-market price of $40 per barrel (price in November 2014). If Iraqi production controlled by IS is incorporated, this revenue stream rises to an estimated $3.2 million per day. Deliveries are mainly to local buyers and to export markets in Turkey. Most deliveries travel by truck and are sold at a steep discount.

Furthermore, it is important to note that there are long-standing grey markets in the region such that a local buyer of several truckloads may even sell to markets controlled by the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG). Reports state, however, that primary buyers are located just across the border in Turkey. There are currently coordinated efforts underway to check the flow of black-market oil from Syria and Iraq, although the historical bootlegging in the region has made this difficult.

In April 2013, the EU agreed to allow oil imports from Syria, although only from moderate opposition groups, which do not currently have access to Syria’s oil export infrastructure. Gas has been of secondary interest given it non-exportability under the current conditions.

As foreign jihadist fighters have moved into Syria, many civilians have fled across its borders. Indeed, Syria has overtaken war-torn Afghanistan as the world’s biggest source of refugees, putting economic strain on its refugee-receiving neighbours.

However, it is the non-refugee movements (militants, jihadists) into neighbouring countries that constitute a serious security threat. For Iraq, this concerns its oil and gas infrastructure, whereas Turkey’s main consideration is the important pipeline system linking eastern supply sources with European markets.

How the Latest Developments May Impact Syria’s Energy Future

It appears that the civil war in Syria has, at least in the medium term, redrawn the map of the Middle East. For energy, this means that the oilfields of north-eastern Syria may well remain in the hands of the Syrian Kurds, with some degree of connection to Kurds in the north of Iraq (the KRG). The territory controlled by the Assad regime (largely Shia Muslim and holding no oil or gas) could potentially become a state of its own. The fate of the rest of Syria (largely Sunni), either under the control of IS or al-Nusra Front, or any other rebel alliance, remains the biggest unknown.

It is hence very difficult at this time to discuss what form the recovery of Syria’s energy sector might take. Syria’s oilfields (with the exception of those targeted in airstrikes) remain relatively unaffected by fighting and sabotage, but the limited options for export and transport have resulted in shut-in production. Prolonged shut-ins can reduce the effective capacity of some fields, and the EIA estimates that Syria’s production capacity – or the level of production that could return within one year – has fallen by nearly 100,000bbl/d since the start of the conflict. Thus, from a strictly technical point of view – assuming the highly complex security situation were to be resolved – production cannot be expected to recover beyond 300,000bbl/d in the near term.

Electricity

Electricity generation and transmission capacity has suffered from the civil war, too. In 2010, Syria generated almost 44 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity, 94% of which came from conventional thermal power plants and the remaining 6% from hydroelectric power plants. By early 2013, more than 30 of Syria’s power stations were inactive, reflecting generation capacity losses upwards of 20%.

Furthermore, at least 40% of the country’s high-voltage lines have been attacked, according to Syria’s Electricity Minister. The night-time satellite images below illustrate the devastation experienced by Syria’s electricity system.

[1] Conventional” excludes what are commonly referred to as “tar sands” or “oil sands”, bitumen mixed with sand and clay that can be extracted with unconventional techniques and turned into synthetic crude oil.

[2] Major producer being defined as more than 100,000 barrels per day of production.