Introduction

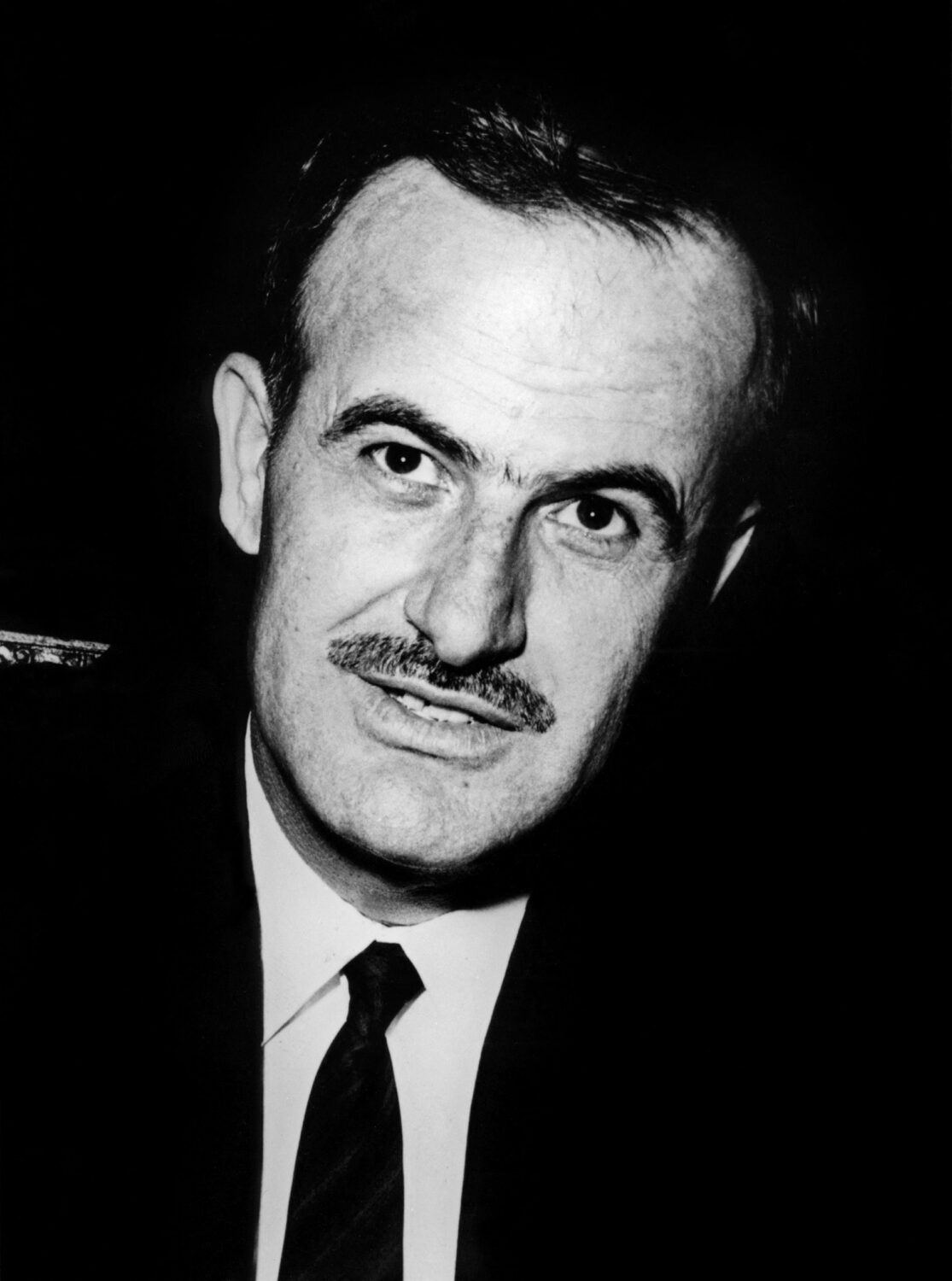

Hafiz al-Assad was far more interested in foreign policy than in domestic affairs, and he is widely considered to have been a master player in the regional and international arenas. Regionally, Syria’s outlook has been deeply colored by its history as a geographical entity embracing all the Levant, which was divided between the French and the British after World War I and then further divided under the French mandate. Under al-Assad, Damascus consistently sought hegemony over its immediate neighbors, and, even when unable to prevail, it proved sufficiently powerful to block the plans of others.

In the wider region, Syria has sought ties with the oil-rich Gulf States which have been important sources of aid, and with Egypt, the region’s most populous and powerful state, although relations with Cairo were not resumed until November 1989, a decade after Damascus severed ties because of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s 1979 peace treaty with Israel, which Syria saw as a major breach of Arab solidarity that would allow Israel to pick off its other enemies one by one.

With Iraq, which was ruled by rival Baathists, relations were generally very strained, and relations with its northern neighbor, Turkey, were uneasy. After the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran, Syria enjoyed a remarkably close relationship with Tehran, underpinned by common hostility towards Iraq and Israel and common suspicion of the West.

Beyond the region, Syria’s stance had been shaped by its regional priorities. Until the collapse of communism in the late 1980s, Syria cultivated close ties with the Soviet Union as a means of countering the West’s apparently open-ended support for Israel, whose creation in 1948 had involved the seizure and ethnic cleansing of Palestine. Damascus hosted thousands of Soviet and Eastern European military and civilian advisers, and the relationship was formalized in 1987 in a 20-year Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation.

The Soviet Union became Syria’s main military supplier, and Russia established a naval facility in the Syrian port of the city of Tartus. However, Syria always kept lines open to the United States and to Europe. The collapse of the Soviet Bloc in the late 1980s was a watershed for Syria, depriving it of its key allies. Al-Assad responded by improving links with the United States.

At the same time, Syria moved to develop its relations with Europe and the European Union (EU), which it saw as a crucial source of financial aid and, potentially, as a mediator in the conflict with Israel that would be less biased than the United States.

Often – and routinely in the 1980s – Syria used violence as a foreign policy tool and, although it paid a price in Western political and economic sanctions, this undoubtedly boosted the international perception of Syria as a state that could not be ignored.

The June War of 1967

Israel and the fate of the Palestinians have been foreign-policy priorities since independence, with successive Syrian regimes linking their legitimacy to their ability to defend Palestinian and Arab rights against the Israelis, restoring the rights of Palestinian refugees, confronting Israel as a colonial entity, and resisting Israeli hegemony.

Syria, which had played a limited and unimpressive role in the 1948 War in Palestine coinciding with Israel’s establishment, signed an armistice agreement with Israel in 1949 but remained in a formal state of war with the new state. Occasional border clashes occurred, often resulting from Israeli provocations.

Liberating Palestine was central to the rhetoric of the Baathists who took power in Damascus in 1963, but their actual performance was dismal. Syria stumbled into the catastrophic June 1967 War with Israel at a time when its Armed Forces, poorly equipped and fatally weakened by political purges of officers, were ill-prepared for conflict.

The Arab defeat, in which Syria lost the Golan Heights, Egypt the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula, and Jordan the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, spelled the end for the radical civilian wing of the Baath, which had ruled in Damascus since 1966. Hafiz al-Assad, who had been Defence Minister at the time of the 1967 defeat, staged his ‘Corrective Movement’ in November 1970.

The October War of 1973

Recovering Arab pride and Israeli-occupied territory were the objectives of the October 1973 War that Syria launched in concert with Egypt. No territory was recovered by either, but both the Egyptian and Syrian forces, transformed since 1967 by major Soviet military aid programmes, performed creditably, inflicting serious losses on the Israelis.

Arab self-respect was restored, and the war was hailed as a triumph in the region, boosting al-Assad’s popularity. It ended with UN Security Council Resolution 338, itself incorporating Resolution 242, which had ended the 1967 War and which affirmed the right of ‘every state in the area’ to live in peace. Syria had previously rejected 242; by accepting 338 it formally accepted for the first time Israel’s right to exist.

Regaining the Golan Heights

Regaining the Golan Heights has since been a key Syrian objective, even though Damascus, recognizing Israel’s military dominance, has tried to avoid direct military conflict. While supporting Lebanese and Palestinian militias fighting the Israeli occupation of Lebanon, Damascus focused on diplomatic solutions to the Golan issue. During the 1990s the Syrians indicated clearly that they envisaged a settlement involving a full Israeli withdrawal from the Golan Heights in exchange for a formal peace treaty with Israel.

Syria took part in ultimately abortive talks aimed at securing a comprehensive Arab-Israeli peace settlement that started in Madrid in October 1991 and Israeli-Syrian negotiations, mainly through US intermediaries, continued for much of the 1990s. The May 1996 election victory of the hard-line Likud bloc, headed by Benjamin Netanyahu, interrupted the Syrian-Israeli talks, as Netanyahu was committed to Israel’s retention of the Golan.

The return of Israel’s Labour Party in the May 1999 election brought a revival of talks with Syria, and, by the end of that year, intensive negotiations were under way that included a face-to-face meeting in Washington of the two countries’ Foreign Ministers and a March 2000 summit meeting in Geneva between Presidents Bill Clinton and Hafiz al-Assad.

Although Syria and Israel failed to reach an agreement, the stumbling bloc being Israel’s demand to annex a narrow sliver of Syrian territory on the eastern shore of Lake Tiberias (under international law, this would give Israel complete control over the lake’s drainage basin), Syria’s commitment to a negotiated settlement was clear.

Policy towards the Palestinians and Lebanon

Syria has always portrayed itself as a champion of the Palestinians, but it has worked ceaselessly to gain hegemony over the Palestinian guerrilla movement that arose in the mid-1960s, after the abject failure of Arab governments to secure any restitution of Palestinian lands or rights. Syria was intent on not being isolated by any PLO-Israeli accommodation, and it was therefore aghast at the ill-fated Oslo Accords, negotiated in secret and signed in Washington in September 1993.

Lebanon, considered by Syrian regimes to be a part of the national territory that had been severed by the French, was another key focus of President al-Assad’s regional interventions. In 1975 Civil War erupted in Lebanon, pitting a Christian/rightist alliance, increasingly backed by Israel, against a Muslim/Palestinian/leftist coalition loosely backed by Damascus.

Apparently fearing the emergence of a radical leftist state on his flank and the potential that this might create for Israeli intervention, al-Assad sent his army into Lebanon in June 1976 at the request of the Beirut government, to help reverse Muslim gains, which they did. They remained there until forced to leave after the assassination of Lebanese ex-premier Rafic Hariri in 2005.

The complex conflict in Lebanon increasingly evolved into a conflict between Syria and Israel, acting through their local proxies. Israeli influence reached a climax in 1982 with a full-scale invasion and the installation of a Maronite regime in Beirut. Slowly and doggedly, Syria and its local allies, notably including the Iranian-backed Hezbollah (Party of God) militia, managed to turn the tide.

In September 1990 a new political settlement was imposed, giving greater representation to the Muslims, and in October that year the last Christian military resistance was crushed. Syrian hegemony over Lebanon was enshrined in a Treaty of Brotherhood, Cooperation, and Coordination signed by Hafiz al-Assad and his then Lebanese counterpart Elias Hrawi on 22 May 1991. In May 2000 the Israelis, smarting from their losses in a sustained guerrilla campaign, finally pulled their occupying troops out of Lebanon.