Introduction

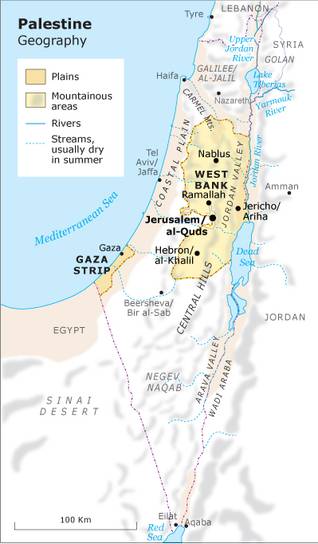

The West Bank and the Gaza Strip differ greatly geographically. The Gaza Strip is a coastal area, with beaches and sand dunes (up to 40 metres high); inland, parallel to the coast, a strip of fertile land makes way for a sandstone mountain ridge. About halfway, the Gaza Strip is intersected by the Wadi Ghazza (Gaza River), which is only replenished with water during the rainy season in the winter (running dry for the rest of the year).

The West Bank is part of a geological formation which stretches from East Africa via the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aqaba and the Wadi Araba (Arava Valley) to Lebanon and Syria, and which is made up of a deep fault line in the earth’s crust. Two mountain chains run parallel with this fault line close to the West Bank. In between lies the Jordan Valley, which is more than 20 kilometres in width (in Lebanon, the Beqaa Valley or Wadi al-Biqa is situated between the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon mountains). The Jordan Valley makes up about a third of the surface area of the West Bank.

The medium-high mountain chain in the West Bank can be sub-divided into three segments: the mountains of Jabal Nablus (Nablus), Jibal al-Quds and Jabal al-Khalil (Hebron). There are various medium-high mountain peaks, of which al-Arsour (in the Jibal al-Quds) is the highest at 1,016 metres. To the east, the mountain range is flanked by the Jordan Valley. Gradually declining, sloping hills stretch westwards, with terraced agriculture in many places.

Climate

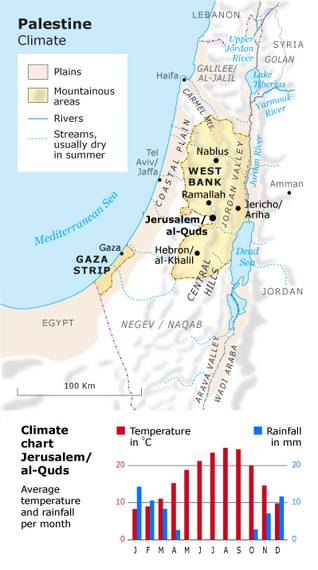

The West Bank and the Gaza Strip are situated in the eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea. The Mediterranean climate is characterized by dry, hot summers and mild, wet winters. The average temperature is 19 ºC, with highs of about 40 ºC in June and lows in January, when temperatures are just above freezing. There is rainfall in autumn and winter, amounting to about 400 millimetres per year.

The West Bank lies more inland, and is marked by regional differences. Although the average temperature is 19ºC in the West Bank, the south is colder (-4 ºC) than the north, where it seldom freezes. In summertime, the temperature can reach highs of 40ºC in both regions, sometimes even a few degrees higher in the Jordan Valley. Entering the Jordan Valley from the west, the drop or rise in temperature is always palpable. Rainfall and sometimes (wet) snowfall occur in the autumn and winter, again on average about 400 millimetres per year.

In springtime, the khamsini, a dry, warm easterly wind, often blows from the extensive deserts of Jordan, Syria, and Saudi Arabia. This continues for a period of roughly fifty days – khamsini is Arabic for fifty – from the beginning of spring until 25 March. The khamsini carries fine desert sand that lends the sultry air an ominous yellow hue during the day. The desert sand falls to the ground as a result of short rain showers. The fine sand is a health hazard for people suffering from bronchitis, and is detrimental to vegetation, motors, and machinery.

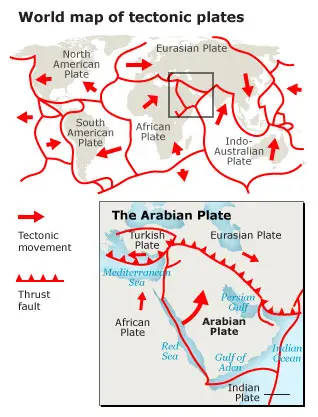

Earthquakes

Earthquakes are caused by the build-up of pressure in the fault line in the earth’s crust, where the African and Arabian tectonic plates run up against each other. Light earthquakes are registered at regular intervals. Historical chronicles also mention strong earthquakes, such as in 746, 1016 and 1034 CE, which on various occasions severely damaged the Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem – one of the most important Islamic sanctuaries. This explains why these events were recorded.

On 1 January 1837, disaster struck again. The earthquake’s epicentre was located at Safad (Safed), north of the West Bank. According to scientists, the quake must have measured 6.5 on the Richter scale, which is in the heavy earthquake category. Some Palestinians can still remember the earthquake of 11 July 1927.

This time, the epicentre was south of Ariha (Jericho), in the West Bank. The quake measured roughly the same as in 1837. Between 250 and 500 died in the area, and there was extensive material damage, especially in the city of Nablus.

The dome of the Aqsa Mosque and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, both of which are in Jerusalem, were damaged. It was Palestine’s most severe earthquake in the 20th century.

Palestine has since become a densely populated region. In Palestine, buildings are not earthquake-proof (nor are they, in general, in prosperous Israel, as of yet). Experts fear that future heavy earthquakes would result in a much higher number of fatalities and casualties than in 1927.

Biodiversity

In concurrence with the changing landscape (coast, mountains, hills, valleys, rivers) there is a rich biodiversity in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The fertile soil, the water, and the mild climate yield a richly varied flora. Around 2,700 plant species have been identified. In spring, the broom and the rockrose blossom in the open; in autumn wild daffodils, crocuses, and hyacinths grow. Common tree species are the olive tree (‘the mother of all trees’), the almond tree, the pine, palm, pomegranate, and cypress, as well as various species of citrus trees and conifers. Bougainvillea, jasmine, and grapevines grow in many gardens but also in the open.

Palestine’s fauna is also rich in diversity. There are about 500 different bird species, of which a quarter are migratory birds, en route from Europe to Africa, south of the Sahara. The pelicans, stopping over on the coast of Gaza, are eye-catching. Scientists have also registered 115 different mammals and 90 different kinds of reptiles. In the Mediterranean Sea and various rivers one can find 285 species of fish.

Water

The water situation in Palestine (the West Bank and Gaza Strip) is dire. Characterized by a shortage of supply, restricted access and poor quality, it affects the quality of life, health and economic situation of every Palestinian.

The water crisis in Palestine is caused not only by the area’s aridity and current agricultural practices. A difficult situation has been made worse by Israeli occupation policies and practices, which prevent Palestinians from controlling their own water resources.

Palestinian water demand in the West Bank and Gaza Strip has been increasing steadily over recent decades. However, Palestinians have been unable to maintain existing water resources or develop new ones due to Israeli restrictions on Palestinian access and control of water infrastructure in the West Bank.

Geographically, Palestine and Israel share two groundwater sources (the Coastal Aquifer Basin and West Bank Aquifer system, known as the Mountain Aquifer Basin) and the Jordan River Basin, the latter also shared with Jordan, Lebanon and Syria. After the Israeli occupation of 1967, Palestinian water resources were brought exclusively under Israeli control through a series of Military Orders. Palestinians have thus been denied access to their rightful share of the available water and been severely restricted in their ability to develop their own water resources (Map 1).

By international and regional standards, Palestinians have the least access to freshwater resources. The West Bank ranks lowest among Jordan Basin states in terms of access to water. For example, the average West Bank Palestinian uses around 70 litres per day (L/d). In some rural areas, this amount drops to 20 L/d, which is far below the 100 L/d recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO).

For more on Water in Palestine, please see the Palestine file on Fanack Water.

Segregated Roads

In conjunction with the establishment of the Jewish settlements, a road network was constructed connecting the settlements to one another. Since 1993, Israel has also been constructing so-called bypass roads around the Palestinian population centres. These are accessible only to persons holding Israeli citizenship (the Israeli nationality does not exist), as well as Palestinians holding a Jerusalem identity card, whose cars have a yellow number plate. Palestinians from Palestine driving cars with a white number plate (shared taxis have a green number plate) are forbidden to use the bypass roads. Violation is punished by heavy fines and – in case of repetition of the offence – confiscation of the vehicle and a prison sentence. The construction of the bypass roads was part of a fundamental revision of Israel’s policy towards the West Bank, no longer focusing on total incorporation of the area within Israel, but instead on sectioning off the areas where Jewish settlement had already taken place.

The bypass roads are well-maintained and well-lit, with multiple lanes, often passing through specially constructed tunnels and viaducts. As such, they are the best roads in the West Bank.

There are secondary roads for the Palestinians, often meandering through the hills and suburbs, which are generally badly in need of repair. At the junctions where the secondary and bypass roads cross one another, the latter always pass under the secondary roads, thus creating a route which can be closed off in periods of heightened political tension, halting the through traffic. By placing hundreds of obstacles on the road (concrete blocks, earthen walls), the through traffic is channelled along roads which eventually lead to one of the many permanent checkpoints manned by the Israeli occupying forces. There are also so-called random or flying checkpoints (i.e. checkpoints which can be set up at random for a couple of hours).

The construction of the bypass roads has led directly to a substantial loss of Palestinian territory. For example, there is a buffer strip of 50 to 75 metres on both sides of the bypass roads, where building is forbidden. As a result, every 100 kilometres of road swallows up about 10 square kilometres of territory. In 2007, 1,661 kilometres of roads were constructed, leading to the confiscation of 166 square kilometres of Palestinian land for this purpose. According to Israel, the construction of the bypass road network is predominantly the result of security concerns. At the same time, the project is part of a bigger scheme to extend Israel’s grip on the area.

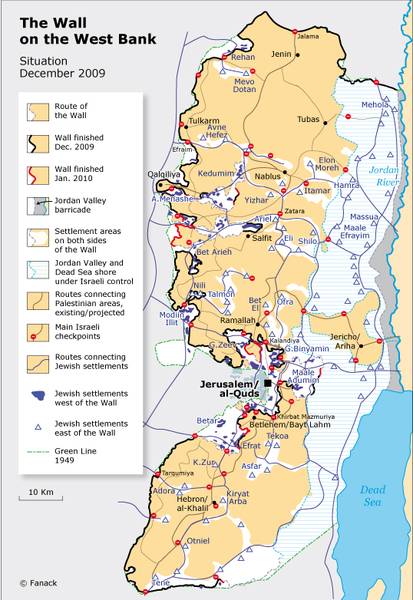

The Wall

Since 2002, Israel has been constructing a separation barrier in the West Bank on the west side, stretching across more than 700 kilometres and consisting of a wall 8 metres in height, though in most places it is a fence. The fact that the Wall (al-Jidar) mostly runs through Occupied Palestinian territory can be deduced from its length: it is almost twice the distance of the border between Israel and the West Bank. On either side of the Wall is a strip measuring 80-100 metres in width where it is forbidden to erect buildings. In various places the Wall runs adjacent to or cuts across the built-up area, thereby severely infringing upon the Palestinians’ living environment. Many Palestinians have also been severely hit as a result of loss of farmland (Israel thus de facto annexing another 10 percent of the territory in the West Bank). Consequently, the landscape looks grim. Previously placed walls and fences had already completely cut off the Gaza Strip from the outside world, against the background of the escalation between Palestinians and the Israeli occupying forces.

ICJ Advice

Palestinians have submitted the question of the construction of the Wall to the world’s primal judicial organ of the United Nations, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), based in the Peace Palace in The Hague (The Netherlands). On 6 May 2004, the Court issued an Advisory Opinion, which is non-binding on UN Member States (as the Court does not issue rulings) but which carries the weight of a binding ruling. In its Advisory Opinion, the Court states that the construction of the Wall and the construction of Jewish settlements are in violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention. The Court found that Israel must immediately cease the construction of the Wall and repeal or render ineffective all measures taken which unlawfully restrict or impede the exercise of the rights of the inhabitants of the West Bank; furthermore, Israel was found to be under an obligation to make reparation for all damage caused.

For the Palestinians, the Advisory Opinion is a mile stone in the recognition of their rights – on the level of international law.

On 2 August 2004, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution ES-10/15 on the ICJ Advisory Opinion, by a vote of 150 in favour and 6 votes against (and 11 abstentions).