Palestinian Refugees - Sixty years after their exodus, Palestinian refugees constitute the 'oldest' and most numerous refugee population in the world...

Introduction

Sixty years after their exodus, Palestinian refugees embody the very essence of ‘refugeeness’. They constitute the ‘oldest’ and most numerous refugee population in the world. Estimated at over 720,000 in 1949, they represent, together with their descendents, a population of over six million today.

Two-thirds are currently registered with a United Nations humanitarian agency especially devoted to catering for their basic needs: the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for the Palestine Refugees in the Middle East (UNRWA). This agency operates in the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

The ‘Palestinian Refugees’ section is part of Fanack’s Human Rights & International Law coverage within the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict.

Stumbling Block

Palestinian refugees have received exceptional media exposure due to their involvement in the conflicts that have scarred the Middle East. The ordeals suffered by Palestinian refugees in Iraq since 2003 simply echo the refugee communities’ fate in Lebanon during the Civil War in that country (1975-1990) or in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in the context of the Israeli occupation since 1967. At the same time, the Palestinian refugees’ attachment to their ‘right to return’ is often considered a major stumbling block in the Israeli-Palestinian Oslo Process. Across the Middle East, the Palestinian refugees’ overall impact on the host countries has been ambivalent: while it is generally recognized that they have contributed positively to their socio-economic development whenever they have been given the opportunity to do so, the poorest refugees – and more especially the refugees in the camps – have been portrayed in terms of a threat to the economic, social and political stability in the host country. This is especially the case in Lebanon, where camps are not covered by the host country’s security apparatus, and have served as a haven for Palestinian military factions and unlawful militias.

Yet, for all their public exposure, available information about the Palestinian refugee issue is fragmented at best, contradictory at worst. This stems first from the ambivalent status of the Palestinian refugee issue as both a humanitarian and a political issue. It also results from the absence of any international definition of the Palestinian refugees and the ensuing uncertainties about their exact numbers. The only available database concerns the 4.7 million refugees registered with UNRWA on purely humanitarian grounds the ‘Palestine refugees’. It excludes all those non-registered refugees, for instance, those who did not reside in one of the Agency’s countries of operation. A third source of confusion derives from the various legal statuses that have been conferred on the refugees by the Arab host countries – from formal citizenship in Jordan to foreigners in Lebanon. In each of the host countries the refugees have been divided into various social subcategories – camp versus non-camp refugees, for instance.

Despite this diversity, the Oslo Process has treated the refugees as one unitary group, subjected to stereotypical integration options in terms of repatriation to Palestine (mainly the future Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip), permanent resettlement in the present host country or a third country, and compensation. However, neither the main host Arab countries, nor the refugee communities have so far had a voice in the bilateral (and mostly secret) Israeli-Palestinian talks. This has undoubtedly contributed to casting doubt upon the relevance and practicality of any Israeli-Palestinian peace plan.

How can we account for the diversity of the refugees’ experiences sixty-three years after their departure from Palestine? To a great extent, while the Palestinian refugees’ situation is influenced by current opportunities and constraints specific to their host country in the context of war or of a stalled peace process, it is still heavily determined by decisions that were taken by the main stakeholders involved in their ‘management’ in the wake of their exodus. It is therefore important to offer an historical account of the institutional framework that was put in place at the United Nations and in the Arab countries in the wake of the 1948 Arab-Israeli war in order to define the Palestinian refugees’ modalities of integration. Also there is the question how the peace process has altered the status quo upon which the relationship between the Palestinian refugees, their leadership, the host countries and UNRWA was predicated, especially with respect to the significance of the right of return.

The Exodus from Palestine

Following the first Arab-Israeli War (1948-1949), the bulk of the Muslim and Christian ‘Arabs from Palestine’ residing in the regions that were to form Israel’s territory lost their homes and their means of livelihood. The term ‘Arabs of Palestine’ was used during the British Mandate period to designate the Muslim and Christian communities. It remained part of the United Nations lexicon until the late 1960s.

The Palestinians’ exodus started as early as November 1947, when the first skirmishes between Palestinian and Jewish militias broke out throughout the country. It reached a peak from April to July 1948 (namely from the weeks that preceded the declaration of Israel‘s statehood to the time when the main Palestinian cities surrendered), when over 300,000 Palestinians went into exile. The last 1948 Palestinian exiles were the inhabitants of al-Majdal Asqalan (Ashkelon), who were expelled in early 1951. In 1949, the remaining Arab population in Israel amounted to 158,000, versus a Jewish population then estimated at 901,000.

The origins of the Palestinian refugee problem, one of the most sensitive issues in the historiography of the Arab-Israeli conflict, are of crucial political importance, since they address the question of responsibility for solving this problem. Ever since 1948, the Israelis and the Palestinians have tried to impose their own narrative. Successive generations of Israeli officials have maintained that the Palestinians left their homes on the orders of their own leaders, or voluntarily. On their part, the Palestinians contend that they were expelled – or transferred – forcibly from their homes. Tapping into a wealth of previously classified state and private papers, a number of Israel’s so-called New Historians have, since the mid-to-late eighties, challenged the official version of a voluntary exodus. Yet, they have not been able to reach a consensus. Some have given credit to, and even reinforced, the Palestinian narrative, shedding light on the existence of a pre-prepared transfer plan. Others have contended that forcible transfer and expulsion measures were just one of a series of factors that also included psychological warfare and fear of Jewish attacks.

Be that as it may, the core issue is not so much the conditions of departure, but Israel’s refusal to allow the refugees to return to their homes, in accordance with the provisions of relevant international law.

The role of Israel in the creation of the refugee problem must indeed be considered in the light of the measures its leadership adopted as early as 1948 in order to secure the perpetuation of its Zionist project. These have included the destruction of nearly two-thirds of over 400 abandoned Arab villages as well as the adoption of a set of legal regulations aimed at expropriating the Arab landowners. Amongst these stand the Emergency Regulations on the Cultivation of Abandoned Lands (June 1948) and on the Absentees Property (December 1948) that were later embodied in the December 1950 Absent Property Law, under which the refugees’ properties were nationalized. In 1953, the Land Acquisition Law further allowed the confiscation of land for military and Jewish settlement purposes.

Right of Return of Palestinian Refugees

In light of the international instruments, it is clear that the expulsion of Palestinians from their homes and lands since 1948 is a violation of the obligations of Israel under international law. Restitution is a form of restorative justice allowing the Palestinian victims to return, as far as possible, to their former situation before the violation of their rights. In the case of the loss of housing and land experienced by the Palestinians displaced in 1948 and in later conflicts between Arab countries and Israel, especially in 1967, restitution is understood as the return of property that Palestinians lost, so that the returning refugee re-acquires the title and actual possession of the lost property. The remedy of compensation should only be envisaged under international law when ‘restitution is not possible or when the injured party knowingly and voluntarily accepts compensation in lieu of restitution’.

Although many United Nations (UN) resolutions hold Israel responsible for the fate of Palestinian refugees and request their return to their homeland, Israel has refused to comply with its obligations and continues a policy of illegal displacement and expulsion of Palestinians. The UN recognized the Palestinian right to return in 1948 in Resolution 194 (III) which states in paragraph 11 that ‘the refugees wishing to return to their homes and live at peace with their neighbours should be permitted to do so at the earliest practicable date, and that compensation should be paid for the property of those choosing not to return and for loss of or damage to property which, under principles of international law or in equity, should be made good by the Governments or authorities responsible’. The Arab countries were originally reluctant to accept this resolution because they feared this would imply recognition of the State of Israel. In the spring of 1949 their position reversed and they consequently adopted the resolution as part of their policy towards Israel.

Since then Resolution 194 has been reiterated by the UN on an almost annual basis. For the Palestinians, the right of return stated in the resolution is still at the heart of any peace talks aimed at resolving the conflict with Israel. It is ‘central to the Palestinian national narrative of struggle against overwhelming odds of expulsion from the ancestral homeland, of dispersion and of national constitution’. The attitude of both parties to the conflict has been diametrically opposed since the Lausanne Conference, in 1949, when members of the UN General Assembly held the position that Resolution 194 was the basis for the solution of the refugees’ problem.

Israel’s Response to the Right of Return

Successive Israeli governments have strongly opposed the idea of the return of the Palestinians and have vehemently justified their position, considering it as an equivalent to the suicide of the Jewish State. The first Basic Law of Israel, the Law of Return, provides exclusively for Jews from all over the world to immigrate to Israel. Consequently, Israel has adopted a policy that categorically rejects repatriation and views resettlement of Palestinians in Arab countries as the only answer to the refugee problem.

The Israeli government has frequently reiterated the stance taken in 1949, namely that ‘UN Resolution 194, like all other resolutions of the UN, is not binding and there is no basis in international law for the right to return’. Israel has refused to acknowledge ths right, despite repeated criticism by the Human Rights Committee on Israel’s refusal to allow the Palestinians to return in conformity with its obligation as a member of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

The fact that the Law of Return applies solely to Jews regardless of their place of origin, is defended by Israel on ideological grounds which are at the heart of Zionism: ‘The law of return personifies the essence of the Jewish State as a Jewish and democratic state.’ Furthermore, it has stated that its immigration policy is a domestic matter and that it has the right to deny Palestinians the same return rights as Jews enjoy under the Law of Return.

‘Right of return’

In 1992, The Jerusalem Post reported the following significant words of Yitzhak Shamir, at that time Prime Minister of Israel: ‘…The term “right of return” is an empty phrase that is utterly meaningless if meant for Palestinians. It will never happen, in any way, shape or form. There is only a Jewish right of return to the Land of Israel.’

Since 1948, Israel has repeatedly stated that it is only willing to allow the return of a limited number of refugees on humanitarian grounds. Essential and inherent to the ‘humanitarian’ motives is the denial of any responsibility towards Palestinian refugees. Since the creation of the State of Israel, this denial of responsibility has been based on two sets of arguments.

First, Israel states that the problem was caused by the refusal of the Arabs and Palestinians to accept the UN Partition Plan in 1947, and second, by the subsequent declaration of war on Israel. Before and during the Arab states’ attack on Israel, Palestinians would have been urged to leave Palestine and come back once the war was over. Moreover, the refugee problem could have been solved if the Arab states which hosted Palestinian refugees had absorbed them. The admissibility of the transfer of Palestinians to Arab states and their assimilation in these countries has always been an important ‘solution’ proposed by Israel for the refugee problem.

Refusal

After 1967, the Palestinian land annexed by Israel in 1948 was completely ignored in the on-going and proposed peace talks, both by Israel and international mediators. The solution of the conflict concentrated on the 22 percent of Palestinian land represented by the West Bank and Gaza. The right of return to the 1948 Palestinian land was completely removed from any peace agenda. Attempts by different peace negotiators to forget about Palestine and concentrate on the West Bank and Gaza, thus allowed Israel to end any discussion of the right of return and retain Palestinian properties seized in 1948. However, for the Palestinians, the events of 1948 remain at the heart of the matter. They reason that an end to the conflict can only be reached by addressing the wrongs perpetrated on Palestinians in that period.

Israel has occasionally accepted the repatriation of a limited number of Palestinians. This was the case during the conference of Lausanne in May 1949 when Israel agreed to the repatriation of 100,000 Palestinians to their homeland in a final peace settlement. However, repatriation of this number never took place, and Arab countries and Israel sparred over the implementation of the protocol almost immediately after signing it. According to Israeli historian Ilan Pappé, Israel agreed to it because it was a condition of UN membership. Once Israel was admitted to the UN, it retreated from the protocol it had signed since it was completely satisfied with the status quo, and saw no need to make any concessions with regard to the refugees.

One of the arguments used by Israel to refuse repatriation was that there had been an enormous increase in the Jewish population, which was mostly housed in abandoned Arab towns and villages. Therefore, ‘it was clear that the individual return of Arabs to their former homes would be impossible. The whole Arab economic system was gone and could not be restored. The Arab middle class, such as shopkeepers, tradesmen and free professionals, could no longer return; their houses and jobs were gone. Their previous means of livelihood have vanished with the disintegration of their economic organization.’

Refugee Camps

The dangerous flight and loss of goods and chattels were traumatic experiences for those involved. Palestinians refer to the events of 1948 as al-Nakba (the Catastrophe).

Only a small number of refugees managed to find shelter with family or relatives. Others found shelter first in public buildings such as schools and mosques. Eventually, the great majority ended up in camps, which had been set up hastily by the United Nations Relief for Palestine Refugees (which in May 1950 became the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, UNRWA), by the International Red Cross and by Christian aid organizations such as the Quakers.

Some refugees were forced to spend years in camps, living in tents at the mercy of the elements. Afterwards, the tents were replaced by so-called shelters – temporary accommodation, measuring only a couple of square metres. The Palestinian refugees initially opposed the construction of these shelters as they seemed to make their situation permanent without resolving anything.

The situation indeed remained unresolved. On 11 December 1948, the General Assembly of the United Nations passed Resolution 194, but the State of Israel (its membership of the UN was subject to the endorsement of the resolution) blocked the return of Palestinian refugees from day one (most of them ended up in neighbouring countries), apparently for security reasons. In reality, however, the campaign of ethnic cleansing was aimed at constructing a predominantly Jewish composition of Israel’s population.

Three Generations of Refugees

In order to be eligible for help, the Palestinians had to register as refugees with the UNRWA. Today, more than three generations of Palestinians are dependent on the UNRWA for their survival – for housing, food, medical aid, and education.

In the early years, life in the camps was extremely harsh for the refugees. To a large extent, the original inhabitants in the Gaza Strip suffered equally, as their lives were often totally disrupted by the huge influx of refugees. However, they were not eligible for aid or support from international organizations, which was available solely to refugees.

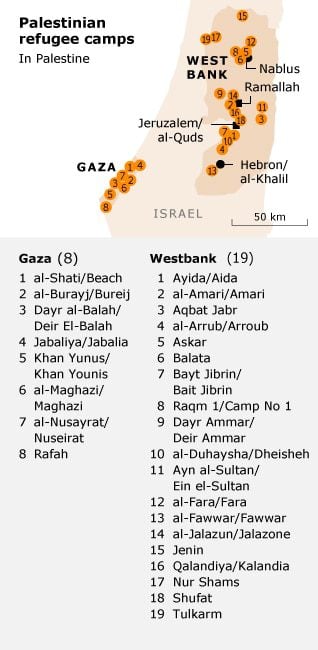

Together, scattered across the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, a total of 27 refugee camps were carved out of the ground after 1948: 19 in the West Bank, 8 in the Gaza Strip. In 2012, the number of inhabitants varied from 1,900 (Ayn al-Sultan, near Jericho) to 110,000 persons (Jabaliya, north of Gaza City), according to UNRWA. Most of the camps are located in the vicinity of the large cities; some have merged with them. Still, these ‘city quarters’ remain easy to detect with their dense streets, inferior infrastructure, and the general absence of parks or other planted areas.

Although the West Bank is fifteen times the size of the Gaza Strip, the number of refugees in camps in the West Bank was less than half that in the Gaza Strip in 2012 (188,150 versus 518,000).

Nevertheless, certainly not all Palestinians ended up in refugee camps after 1948. Those who had enough money, family support, or who were simply lucky, could rent or buy a house or apartment in a new place of residence.

During the June War of 1967 and the ensuing occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip by Israel, many thousands of Palestinians were again forced to seek refuge elsewhere: about 250,000 left the West Bank and 70,000 left the Gaza Strip. Most of them ended up in Jordan. Others who were abroad when war broke out, were denied access to the territories.

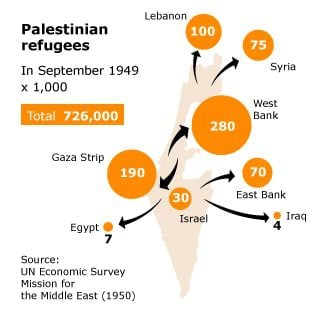

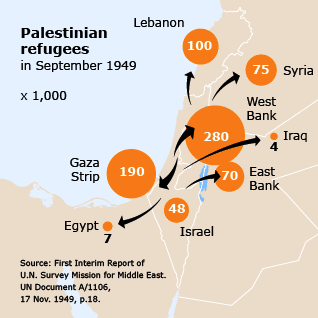

Palestinians as Specific Refugees

Estimates of the ‘1948 refugees’ vary from a low of 520,000 (initial Israeli official estimates) to a high of 850,000-900,000 (initial Palestinian sources). However, most observers today concur that the estimates of the United Nations Economic Survey Mission (ESM) are the most accurate. According to the ESM, in September 1949 the total number of refugees did not exceed 774,000, including 48,000 displaced persons in Israel proper: 17,000 Jews and 31,000 ‘Arabs from Palestine’. The remaining 726,000 refugees settled in neighbouring Arab territories (see infographic). Out of the total of 774,000 refugees, it was estimated that 147,000 were self-supporting, bringing some 625,000 refugees in need of relief assistance.

From the outset, the Palestinian refugees have been categorized by the international community, including the Arab countries, as a specific refugee category. Indeed, both the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the UNHCR Statute of 14 December 1950 exclude those refugees who ‘are at present receiving from organs or agencies of the United Nations other than the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees protection and assistance’ (article I.D). This was the case for the Palestinian refugees registered with UNRWA. Although the Palestinian refugees are not mentioned explicitly, the discussions preceding the adoption of the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the UNHCR Statute indicate that UNRWA-registered refugees were the one group of refugees targeted by the exclusion provisions on political grounds.

While the Western countries were concerned that the very sensitive Palestine refugee issue would burden the UNHCR mandate, the Arab countries insisted that the Palestinian refugees be treated, not as any other humanitarian refugee group, but as a specific group to which the United Nations Organization was politically committed on account of its involvement in the creation of the refugee problem. The fact that UNRWA’s humanitarian mandate was limited to the provision of basic services (primary and vocational/technical education, health care and social services) and did not include any of the UNHCR’s human rights protection activities did not raise any concern at the time. Political considerations prevailed.

Moreover, it was believed that the Palestinian refugee issue, at least its humanitarian aspects, would be settled in the short term. The 1951 Convention included, for that matter, an ‘inclusion clause’ ensuring the automatic entitlement of refugees benefiting from the protection of the 1951 Convention if, without their position being definitively settled in accordance with the relevant UN General Assembly (UNGA) resolutions, assistance from UNRWA had ceased. The perpetuation of the Israeli-Arab problem, and the ensuing extension of UNRWA’s mandate, turned the refugees’ status into a liability whenever they were mistreated or discriminated against by the host countries.

The protection gap proved all the more extensive as it eventually covered all Palestinian refugees living in the Middle East, including those not registered with UNRWA. Of the attempts made by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), or by human rights groups from the 1980s onwards, to have the UNHCR and/or UNRWA extended in order to protect the Palestinian refugees’ existence, none succeeded. This was the case during the various episodes of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990) and during the Second Intifada (since 2000). Both UNRWA and the UNHCR have forcefully insisted on the operational (the former) and administrative (the latter) limitations of their mandates.

UNRWA as the Main UN Stakeholder

UNRWA‘s unique institutional and operational characteristics have also contributed to singling out the Palestinian refugee issue. The Agency was created as a result of UNGA resolution 302 (IV) of December 1949. A temporary humanitarian agency, it was tasked to pursue the international emergency relief programs started in 1948 in order to secure the survival of needy refugees (until December 1950), and contribute to their socio-economic reintegration through public works programs (until June 1951) in five operational territories: Jordan, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, Lebanon, and Syria.

Social Support Program

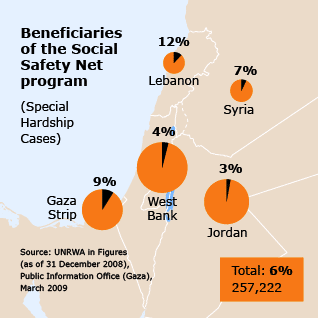

After its public works programs failed to induce the collective reintegration of refugees in the host countries in the early fifties, the Agency strove to adapt its general educational, health, and relief and social programs to the evolving needs of an ever growing registered refugee population. With unsustainable financial resources, UNRWA’s relief and medical services helped the refugee communities to recover from the ordeals of forced migration displacement, including starvation, and vector-borne or water related communicable diseases. Simultaneously, the Agency’s primary education and vocational/technical training programs gradually enabled them to move from total dependency on UNRWA’s rations towards self-sufficiency, thus contributing to the individual integration of many second and third generation refugees in the wealthy oil economies of the Middle East or within UNRWA’s bureaucracy itself. Since the late 1960s, UNRWA’s education department has been the largest in terms of personnel and budget. In December 2008, it consumed 52 percent of the Agency’s general budget, compared to 19 percent for the Health Department and only 10 percent for the Relief and Social Services Department. Conversely, the Agency’s relief program (food commodities, cash subsidies and shelter rehabilitation), which was the largest in terms of beneficiaries until the late 1960s, today provides benefits to an average of six percent of the registered refugees only, and with significant regional variations: from a high of 12 percent in Lebanon to three percent in Jordan. In absolute numbers, however, refugees in the Gaza Strip form the largest beneficiary cohort, followed by refugees in Jordan.

With unsustainable financial resources, UNRWA’s relief and medical services helped the refugee communities to recover from the ordeals of forced migration displacement, including starvation, and vector-borne or water related communicable diseases. Simultaneously, the Agency’s primary education and vocational/technical training programs gradually enabled them to move from total dependency on UNRWA’s rations towards self-sufficiency, thus contributing to the individual integration of many second and third generation refugees in the wealthy oil economies of the Middle East or within UNRWA’s bureaucracy itself. Since the late 1960s, UNRWA’s education department has been the largest in terms of personnel and budget. In December 2008, it consumed 52 percent of the Agency’s general budget, compared to 19 percent for the Health Department and only 10 percent for the Relief and Social Services Department. Conversely, the Agency’s relief program (food commodities, cash subsidies and shelter rehabilitation), which was the largest in terms of beneficiaries until the late 1960s, today provides benefits to an average of six percent of the registered refugees only, and with significant regional variations: from a high of 12 percent in Lebanon to three percent in Jordan. In absolute numbers, however, refugees in the Gaza Strip form the largest beneficiary cohort, followed by refugees in Jordan.

Despite the shortcomings of its mandate, especially with regard to a lack of general protection, the Agency has often proved indispensable in times of conflict. Through specific emergency relief programs, it has contributed to securing the livelihoods of besieged Palestinian refugees and non-refugees, be it during the Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip (1956), the 1967 June War, the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1991) and, more recently, the two uprisings against the Israeli occupation in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (1987- 1994, and since 2000).

Semi-state

In retrospect, UNRWA is the only UN agency to have worked for such a long time in the exclusive service of one particular category of refugees – the ‘Palestine refugees’. Over the years, it has gradually established itself as a semi-state institution in the fullest sense, taking on responsibilities traditionally assigned to national governments. Its staff, the vast majority of whom come from the refugee communities, has grown fivefold since 1951, from about six thousand to 30,000 in 2009. However, UNRWA’s linkage with the refugees is only predicated on humanitarian considerations. Its definition of a ‘Palestine refugee’ was elaborated for operational purposes only. It did not determine who is a Palestinian refugee, but rather who is eligible for its assistance programs. While it has evolved over time, its core elements have remained the same: normal place of residence in Palestine during the period 1 June 1946 to 15 May 1948, and loss of means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 conflict. Descendents of male Palestine refugees have also been eligible to register on a voluntary basis with UNRWA. Since 1951, the number of ‘Palestine refugees’ has increased fivefold, from 876,000 refugees to 4.7 million refugees in 2008. This represents about 90.8 percent of the total number of refugees in the Middle East; and about three-quarters of the estimated total Palestinian refugee population disseminated around the world.

From the outset, UNRWA’s assistance mandate has been regarded by the refugees not just as a temporary international charity venture, but as an entitlement and, even more, a recognition by the international community of their status as refugees endowed with vested rights, namely the right of return to Palestine and/or to receive compensation as recommended in UNGA resolution 194 (III) (11 December 1948). UNRWA’s identification with the political dimensions of the Palestinian refugee issue may have been reinforced by its status as the only significant UN stakeholder in charge of Palestinian refugee affairs, following the de facto demise of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine (UNCCP) in the early 1950s, and the de jure exclusion of the Palestinian refugees from the UNHCR coverage. As a result, although registration with UNRWA was never officially meant to have any political implications, it has nevertheless been regarded by the refugees as a legal justification for their vested humanitarian and political rights. This is understandable since the ‘registration card’ it provides has constituted an official – and often unique – piece of documentary evidence attesting to their link with pre-1948 Palestine.

Refugees Living in Camps

That identification may also have been triggered by the prevalent perception of the Agency as inseparable from the 58 camps it currently services in coordination with the host authorities. Established in the late 1940s- early 1950s in order to better assist and control scattered groups of homeless refugees – mostly former farmers and labourers unable to afford any decent lodging – camps became the symbols of the refugees’ refusal to settle permanently in their host country, in the name of their ‘right of return’. Yet the percentage of camp refugees across the Middle East (RRC’s) has never exceeded 40 percent since May 1950, stabilizing nowadays at about one third of the registered refugees, with significant variations: from a low of 17 percent in Jordan to a high of 53 percent in Lebanon. In absolute terms, however, the Gaza Strip records the highest cohort of camp refugees (nearly half a million camp refugees), followed by Jordan (338,000 camp refugees), while Syria has the lowest (about 125,000 camp refugees).

The politicization of UNRWA’s mandate has shaped the refugees’ relations with the Agency. Every decision adopted by its management has thus been scrutinized through the prism of its adequacy with regard to the right of return. In this way, the numerous budgetary restriction measures the Agency has been compelled to take as a result of decreases in the financial contributions of its donor countries have chiefly been interpreted as representing a denial of that right.

The Arab Host Countries

The Palestinian refugees’ (temporary) exclusion from the international humanitarian regime in the Middle East has left the host countries free to craft the type of integration policies that best suited their internal political and socio-economic interests. This explains the diversity of the current refugees’ legal statuses and situations across this region. Yet, behind this diversity, it is possible to discern common trends that resulted from recommendations elaborated by the Arab League as far back as the early 1950s.

Maintaining the bulk of the Palestinian refugees in statelessness – officially as stateless, but endowed with a ‘Palestinian nationality’ – was the main measure taken by the Arab countries in order to prevent their full integration and thus preserve their right of return. Jordan, which extended its sovereignty to the West Bank of the Jordan River in the wake of the 1948-1949 Arab-Israeli War, stands out as an exception. Because Jordan’s King Abdullah I believed that the relatively better educated Palestinian refugees would be instrumental in modernizing his kingdom, he decided to grant them, as well as the indigenous inhabitants of the West Bank, full nationality in 1949. This has not, however, prevented Jordan from continuing to support the right of return: once Palestine was liberated, the refugees would be given the option to choose between permanent settlement in Jordan or repatriation to their original homes in a liberated Palestine.

Casablanca Protocol

The Arab League sought to alleviate the refugees’ political marginalization by ensuring, through numerous resolutions, that they would be given treatment on a par with the citizens of the host countries in such socio-economic fields as employment, residency, education and free movement. In particular (except in Jordan) the refugees were granted Refugee Documents in order to facilitate travel and access to employment across the Middle East. In 1965, these various legal instruments were synthesized in one document, the Casablanca Protocol, which was adopted by the Council of Foreign Ministers of the Arab League.

Although the Protocol was ratified by most countries of the Arab League, it has never been fully or consistently implemented. As a matter of fact, the Palestinian refugees have generally been subjected to discriminatory legal/administrative measures applicable to foreigners. The most striking example is Lebanon, where Palestinian refugees, who constitute a sizable percentage of the total population (about 10 percent), have since 1948 been treated as foreigners in such matters as employment, the acquisition and inheritance of property, taxation, and social security. In addition, they have had almost no access to governmental medical, education or social services outside those of UNRWA (or the rather expensive private sector’s) and have been barred from most liberal professions, including medicine, law and engineering, and other ‘protected’ professions (sixty to seventy professions altogether). Suspended after the conclusion of the Cairo Accords between the PLO and the Lebanese authorities in 1969, these discriminatory regulations have been fully enforced upon the Palestinian refugees since the abrogation of these accords in 1987. Even in Jordan, where the ‘Jordanians of Palestinian origin’ – as the 1948 Palestinian refugees are formally labelled – have enjoyed the political and socio-economic benefits of citizenship, a number of informal incidents of discrimination have been reported in the fields of employment in the public sector and of representation in parliament and other national institutions. The fate of the approximately 200,000 ‘Gazan displaced’, namely those 40,000 refugees and non-refugees from the Gaza Strip who were transferred to Jordan in the wake of the 1967 Arab-Israeli war and their descendents, has been far less enviable. Similarly to most Palestinian refugees in the other Arab host countries, they have been kept politically disenfranchised and have been subject to numerous restrictions in regards to ownership of property, access to higher education and to governmental services.

In contrast, Syria has been considered the most equitable towards the Palestinian refugees. Since the 1950s, it has granted them the same rights as its own nationals in the fields of employment, government services, trade and military service, while restricting access to land ownership (to prevent permanent resettlement). Besides feelings of solidarity and generosity towards the refugees, Syria’s generosity may also be ascribed to the fact that the refugees only amount to a tiny portion (2.7 percent) of its total population.

Expenditures to Palestinians

The discriminatory statuses imposed by most Arab host countries upon the Palestinian refugees has been stigmatized by Israeli and Western observers as reflecting the cynical instrumentalization of the refugee question for their own strategic ends within the Arab-Israeli conflict. The Arab countries for their part, have predicated their position on international law and more especially on the international community’s obligation to implement the relevant UN resolutions, starting with UNGA resolution 194 (III).

Internal socio-economic and political considerations have also been put forward. As early as 1960, UNRWA itself acknowledged that the host countries had nowhere near the absorptive capacity needed to integrate a refugee population of that magnitude. Moreover, credit was to be given to assist the host countries in terms of provision of private or state-owned land for camp sites, the enforcement of the rule of law in the camps, and the provision of complementary medical, welfare and educational (post-preparatory phase) services to the UNRWA-registered refugees and full support to the non-registered refugees. Both Jordan and Syria reported that expenditures on behalf of the Palestinian refugees exceed those of UNRWA. In 2004-05, Jordan’s support for the refugees amounted to about half a billion dollars (USD 440 million) compared to USD 73 million for UNRWA.

The same year, Syria’s reported expenditures on behalf of the Palestinian refugees was USD 102 million, compared to USD 28 million for UNRWA. Lebanon’s level of expenditure was lower: approximately USD 30 million, while UNRWA’s stood at USD 55 million. Overall, the total amount of the Arab countries’ contributions to UNRWA’s regular budget has been lower than expected. It accounted for less than two percent (four percent when taking into account special projects), while relevant Arab League resolutions targeted 7.73 percent of UNRWA’s regular budget. This reflects a deeply anchored belief among Arabs that the Palestinian refugees’ humanitarian plight is an international responsibility.