Since ancient times, Palestinians have been farmers, due to the presence of fertile soil and water. In the West Bank, the mountain range stretching from north to south causes rain to fall. The water is caught in aquifers and surfaces in springs. In the West Bank, there are mountain aquifers in the west and east, stretching to the Mediterranean Sea and Jordan, respectively. The tail end of the coastal aquifer is in the northern part of the Gaza Strip. Besides these aquifers, the River Jordan has also been an important source of water since ancient times. However, the water quantity and quality have declined so drastically during the past decades that the river’s contribution to agriculture has greatly diminished.

In the past, farmers lived in an autarkic society. This changed from the middle of the 19th century as a result of increasing trade relations with Western nations. Since then, Palestine has exported products such as grain, citrus fruits, olive oil, soap, but also tapestries and glass work to Western markets via the ports of Jaffa, Haifa, and Acre. Conversely, Western industrial products found their way to the Palestinian market.

This continued during the British Mandate (1920-1948). An important development in this period was also the gradual expansion of a parallel economy by Jewish settlers. Their land purchases not only forced land prices to rise but also drove Palestinian lease holders from their land.

During the war in 1948 (the Nakba), the Gaza Strip and the West Bank were inundated with a huge influx of Palestinian refugees which the economy could not absorb.

Jordanian Period

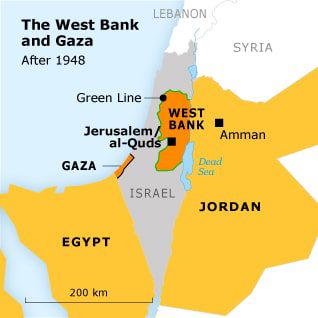

During the War of 1948, Transjordan occupied the West Bank, which it subsequently annexed in 1950. As a result, the region was cut off from the coastal strip with which it was closely tied economically. The West Bank became landlocked. What followed was the West Bank’s involuntary economic orientation on Transjordan (which was called Jordan after the annexation of the West Bank). At the time, Jordan was a desert country in the early stages of its development.

The Jordanian authorities afterwards pursued a policy in which the East Bank was strongly favoured above the West Bank in terms of investments and the construction of an infrastructure. The East Bank developed further, whereas the economy in the West Bank stagnated. A large number of Palestinians were encouraged to settle in the East Bank. Others left for the Gulf States, where the demand for labourers had increased due to rising oil revenues. Some emigrated to North and South America and elsewhere in the world.

In 1948, the Gaza Strip was also abruptly cut off from its economic hinterland. The area was placed under military control by Egypt, which afterwards barely invested in its economy. The void was filled mainly by the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA). In a later stage, Palestinians were offered education and job opportunities in Egypt.

On the eve of the Israeli occupation, half of the working population in the West Bank were farmers or agriculturalists. Nonetheless, they only contributed 25 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP). This was almost the same as the trade sector, wherein far fewer people found employment. Both agriculture and industry were operated by small family businesses.

Israeli Colonization of Palestine

In the June War of 1967, Israel conquered the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. For the second time in two decades, both regions were forced to re-orient economically, this time with far-reaching and paralyzing consequences. Since then, Israel has not only occupied but also heavily colonized Palestine. The outlines of this move were sketched in what is known as the Allon Plan, which was presented to the Israeli government only a month after the cessation of hostilities.

Policy and strategy were to extend Israel’s east border in the direction of the River Jordan, further effectuated by the construction of a series of Jewish settlements in the Jordan Valley. As a result, the large Palestinian community in the West Bank would be cut off from the community in Jordan. The construction of settlements around East Jerusalem would present the annexation of East Jerusalem as a fait accompli.

Israel has systematically expropriated and confiscated land in Palestine after 1967. This policy involved both state land as well as privately owned plots belonging to Palestinians, of which the right of ownership could not be demonstrated conclusively. Confiscation took place based upon military orders, issued by the military government which had been installed directly after the region was taken.

Whole areas of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip were declared ‘Closed Military Area’. These were often highly fertile strips of land, especially in the Jordan Valley and in the north-west of the West Bank, on the border with Israel. 145 Jewish settlements rose on the confiscated land, plus a hundred ‘outposts’ (and the accompanying infrastructure), where about half a million Jewish settlers have since settled.

The far-reaching object was to control as much land and water in Palestine as possible. Annexation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip have never been serious options, as in 1967 that would have meant another million ‘non-Jewish’ citizens within Israeli state borders, making up 30 percent of the total population. The Jewish character of the State of Israel would have weakened as a result. Moreover, Israel would have come into collision with the international community.

Although Israel had got away with the occupation of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, the UN Security Council’s reaction to the annexation of East Jerusalem had made clear that the international community would draw a line regarding Israel’s actions. The unanimous condemnation and refusal to recognize the annexation by the UN Security Council, was underlined by the transfer of the UN members’ embassies from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv.

The outcome of these policies was that between 1967 and 1993, Israel confiscated 38 percent of the territory in the West Bank and 49 percent in the Gaza Strip (mid-2005, Israel withdrew its army and settlers from the Gaza Strip, nullifying the confiscation). As a result of the construction of the Wall, which is 700 kilometres in length and commenced in June 2002, Israel will de facto annex another 10 percent of the territory in the West Bank, including its water resources.

Israeli Restrictions

Before the full dimensions of both developments became clear, an extensive system of permits and licenses was introduced based on military orders. Permits had to be applied for in order to purchase land, construct houses, start a business, and for the transport of goods, all import and export, and so forth. The red tape which came with these permits, and the often sluggish process of the military bureaucracy, drastically curtailed the elbow room of Palestinian businessmen. With the permit system, the Israeli occupying forces also had a weapon to punish Palestinians who in any way restricted the occupation.

After 1967

After 1967, Israel was responsible for structural neglect of the physical infrastructure such as water pipes and the electricity and telecom networks. The same applies to the road network. In the 1980s, it was possible to see exactly where the border was crossed from Israel into the West Bank on the road from Tel Aviv to Ramallah from the quality of the road surface and the absence of street lighting. Palestinian entrepreneurs were disadvantaged by this. Medical and educational services had to call upon foreign financial support. All of this was in stark contrast to the high sums which Israel collected annually as a result of taxes and dues from the Palestinians.

After the Palestinian Territories were conquered, Israel immediately introduced regulations in order to more or less close its own market to Palestinian products and goods. Conversely, heavily subsidized Israeli products and goods could be sold in Palestine. The result was that the Palestinian products were priced out of the market. As Israel gained control over the outer borders of Palestine, it gained complete control over Palestinian import and export.

Palestine soon became the second most important market for Israel, after the United States. Ninety percent of the Palestinian import came from Israel, 70 percent of Palestinian export went to Israel (products and goods which did not compete with Israeli products, or which had been produced by Palestinian subcontractors of Israeli companies. Given that total revenues from imports were twice as great as from export in the 1970s and 1980s, the Palestinian balance sheet showed a severe structural deficit.

Palestinian Labourers in Israel

Paradoxically, during the first years of the occupation, in the period between 1968 and 1972, the Palestinians’ gross national product and purchasing power increased rather than decreased, by an average of 13 percent per year. This was for a number of reasons. In the second year of the occupation, Israel allowed Palestinians to work in Israel – firstly unschooled labourers, especially in construction, afterwards also in industry and agriculture. The workforce was recruited in Palestine by Israeli employment agencies.

The Israeli labour market was keen to employ Palestinian workers as they were willing to work for lower wages than Israeli employees. Nonetheless, Palestinian workers earned more in Israel than under Palestinian employees (if they had employment). However, it was forbidden for Palestinian workers to spend the evening and night in Israel once work was done. They were left no option other than to commute between their homes and the workplace, which was possible given the reasonably short distances involved.

The number of Palestinian labourers in Israel soon rose, according to official numbers, from 20,000 in 1970, to 55,000 in 1972, to 89,000 in 1985, which was the equivalent of no less than 36 percent of the Palestinian work force. Conversely, Palestinian labourers in Palestine never made up more than 7 percent of Israel’s population. Experts estimated the real number of Palestinian workers in Israel to be at least more than 25 percent higher.

A substantial group of Palestinian workers and Israeli employees preferred to conduct business outside the official, bureaucratic channels (circumventing the payment of taxes). From the start, the Palestinian workers in Israel contributed significantly to the Gross National Product (GNP) in Palestine. In 1985, they made up 22 percent of the total for the West Bank, and 37 percent for the Gaza Strip.

Another reason for the increase in purchasing power was the increase in the number of Palestinian workers in the Gulf States after the October War of 1973 and the strong increase in oil revenues of oil producing countries. The money transfers to families left behind subsequently also increased proportionally.

Open Bridges Policy

In addition, immediately after the conquest of the Palestinian Territories, Israel launched its so-called Open Bridge policy (i.e. the bridges across the Jordan) in order to safeguard its own market from Palestinian agricultural products. Within the framework of this policy, Palestinian farmers could continue to export products to Jordan. This stopped the Palestinian economy from completely collapsing, but the ‘Open Bridge’-policy also served Israeli interests. Cheap Palestinian agricultural products were kept out of the Israeli market. By offering the Palestinians an economic breathing space, the political tensions remained controllable in a period when Israel was still consolidating the occupation.

Exports to Jordan were limited mostly to agricultural products. Jordan maintained strict regulations where other products were concerned, driven by the desire to protect its own industry against competition. Moreover, the Arab League had proclaimed a general boycott of Israel, and Jordan wanted to prevent Israeli products from entering the Arab market through a back door.

Growth Without Development

The increase of the GNP paints a distorted picture of the Palestinian economy. The growth went hand in hand with stagnation in the development of the Palestinian economy, caused mostly by restrictive Israeli measures. In both agriculture and industry, small family businesses, using elementary techniques, continued to be the trend. In 1992, their part in the GNP was on the same level as in 1967. The only sector to witness substantial growth was the construction sector, as many labour migrants – partly because there were few economic opportunities – invested in ‘bricks and mortar’ (houses). In other words, economic growth did take place, but economic development remained absent. This further increased the vulnerability of the Palestinian economy.

Over the years, large deficits in the trade balance were plugged with revenues gained elsewhere (Israel, the Gulf States) – not with financial means generated by the Palestinian economy. In other respects, too, these revenues have helped keep the Palestinian economy on its feet.

The vulnerability of the economy in Palestine became painfully apparent in the second half of the 1980s. As a result of sharply decreasing oil revenues, employment opportunities for Palestinian workers in the Gulf States declined. Of course, the First Intifada, which erupted in 1987, also had negative effects on the Palestinian economy. It is noteworthy that the number of Palestinian workers remained more or less stable in Israel in the Intifada years (1987-1993). Their purchasing power did lessen, as a result of the hyperinflation which was present in the Israeli economy at the time. However, most severe were the effects of the expulsion of about 200,000 Palestinian workers from the Gulf States in 1991 as a result of the PLO leadership’s pro-Iraq position during the Kuwait crisis.

The result of all these developments was that the economy in Palestine was completely unbalanced on the eve of the Oslo Process.

After the Oslo Agreement

After Israel had gained full control over the economy in Palestine after 1967 and had wholly subordinated it to the Israeli economy, the hopes and expectations of many grew that the Oslo Process would bring an end to the subjugation and that the bases would be laid for an independent, sovereign, (economically) viable Palestinian state in Palestine. However, these hopes were in vain. Instead, the subjugation continued under a new guise.

Economic Relations Protocol

The basis for this was laid in the Protocol regarding Economic Relations of 29 April 1994, also called the ‘Protocol of Paris’ (named after the place where the negotiations took place). In this, the monetary, fiscal and trade relations between Israel and the Palestinian National Authority were regulated for the length of the Oslo interim period (1994-1999). Based on the Protocol, Israel retained full control over the Palestinian trade and tax revenues.

The difference was that the collected taxes and duties would no longer flow into the Israeli treasury, but would be handed over to the PNA. With this source of income, a substantial portion of PNA expenditures could be financed. This also gave Israel a robust means of putting pressure on the PNA. This was just one area in which Israel continued to dictate proceedings in reality, making the elbow power of the PNA very restricted.

Further Restrictions

Moreover, in the final phase of the First Intifada, Israel began to impose restrictions on the Palestinians in Palestine wanting to enter Israel. From 1993 onwards, Palestinian workers needed to possess a permit in order to be able to work in Israel. From the mid-1990s, other Palestinians could only enter Israel on a permit applied for in advance. Some time afterwards, it was decreed that vehicles registered in the Palestinian Territories were not allowed to enter Israel.

Inside the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, passenger travel and movement of goods were also severely curbed for many years by means of a network of checkpoints which could only be passed by those who held a permit. The measures were dictated by the worsening security situation but also served as a means of putting pressure on the Palestinians in the soon highly tense negotiations between Israel and the PLO/PNA on the further details of the Oslo Accords.

The Result

The result was a sharp decrease in the number of Palestinian workers in Israel in the Oslo interim period, from 116,000 in 1992, to 28,000 in 1996. After the outbreak of the Second Intifada (2000), their numbers further declined, their vacancies now filled by East European and South-east Asian workers. The contribution of revenues from Palestinian workers in Israel to Palestine’s GNP decreased accordingly in the same period, from 25 to 6 percent.

Unemployment rose proportionally. At the same time, the economy in Palestine suffered severely from the long-term closing off of Palestine in periods of heightened political tension, for example after violent clashes or a (suicide) bombing. The same applied to the temporary reoccupation of the several large cities in the West Bank in 2002, bringing great destruction to the infrastructure that had only recently been improved.

Reliance on Aid

For decades, the international community through the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) had aided the Palestinian refugees in Palestine. With the Oslo process, it now became possible to offer the Palestinians aid through other channels than the UNRWA. This was partly dictated by clear self-interest, as it was important to bring under control one of the world’s largest sources of tension. The aid was primarily focused upon setting up the PNA’s administrative apparatus and improving the structurally neglected infrastructure.

In order to get the economy in Palestine back on the rails, from 1994 an appeal was made for the services and aid provided by institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. These advocate a small government and a central role for the private sector in stimulating economic growth. However, on various levels, this was unfeasible due to the intractable situation in Palestine. Job opportunities within the administration increased greatly (up to 25 percent of the working population) – among others, within the police and security services – in order to absorb the huge increase in unemployment as a result of the loss of job opportunities in Israel.

Whereas initially the emphasis was strongly on development, after the outbreak of the Second Intifada and its dramatic effects on Palestine’s economy, the focus was shifted to relief. This especially applied to the Palestinians in the Gaza Strip after Hamas’ election victory in 2006. Afterwards, the new Hamas-led PNA government had to manage without the Israeli contribution of tax revenues and levies, or the assistance of Western states. After Hamas’ assumption of power in the Gaza Strip in mid-2007, a general blockade was further imposed, and at the end of 2008 – beginning 2009, Israel held a devastating military operation.

In order to maintain the (non-constitutional) government of PNA/Fatah in the West Bank, led by the former World Bank and IMF head, all Western funds have since flowed towards the West Bank. For the same reason, Israel allowed Palestinian workers from the West Bank access to Israel once again.

Balance

Palestine’s economy has become a plaything of forces over which the Palestinians have no control. There is no Palestinian administration which can independently give direction to its economic policy and secure its own economic interests. The PNA/Fatah government in the West Bank maintains its position solely due to substantial financial support, especially from Western and Arab states. The Hamas government in the Gaza Strip is supported by financial backers in the Gulf States and NGOs in the Arab and Islamic world.

Many of the economic indicators are unfavourable.

In 2007, production figures in the agricultural sector were 55 percent lower than in 1999. In the same period, production in the manufacturing industry dropped by 20 percent and the building industry shrank by a massive 66 percent. The United Nations noted in a 2012 report that agricultural production has declined by 20-33 percent since Israel enforced a security ban on imported fertilizers. Gross agricultural production value declined from 2,047,000,000 USD in 2008 to 1,445,000,000 USD in 2011, according to FAO.

In 2012, unemployment in the West Bank was 18.3 percent, while in the Gaza Strip it was 38.8 percent. In 2011, 17.8 percent of the inhabitants of the West Bank and 38.8 percent of the inhabitants of the Gaza Strip were living in poverty, according to the Palestinian CBS.

The West Bank’s economic viability has been seriously undermined as a result of confiscation of Palestinian land, the building of Jewish settlements, and the construction of accompanying infrastructure, all of which has fragmented the West Bank, making it much more time consuming to travel from one place to another. In the Gaza Strip, fishing has been almost completely halted by forbidding fishermen to travel far out into the Mediterranean Sea.

A World Bank report published in October 2013 found that Israeli restrictions on Palestinian land (Area C) have resulted in an economic loss of 3.4 billion USD.

The contribution of agriculture in the West Bank to the Palestinian economy has declined. In the mid-1990s, agriculture contributed over 14 percent of GDP; in 2011, it was only 5.1 percent. Due to access restrictions to land and water, predominantly in area C, large swathes of fertile land are not cultivated by Palestinians and development of infrastructure needed for a market-oriented agriculture is constrained. At the same time, agricultural land area cultivated by Jewish settlements has expanded rapidly, growing by 35 percent since 1997 and reaching around 93,000 dunams in 2012.

The Palestinian construction sector has also suffered from limited land available for construction. It is largely confined to areas A and B, which exerts strong upwards pressure on the price of land, buildings and physical infrastructure. UNOCHA estimated that Israel allows Palestinians to construct freely in less than one percent of area C, much of which is already built up. Moreover, Palestinians are rarely granted permits.

Finally, the development of tourism potential in Palestine is hindered by the fragile political and security situation and Israeli restrictions on movement, access and physical development. Private and public investments in tourism have also lagged behind.

According to the American political scientist Sara Roy – the author of two important studies on the Gaza Strip – the relationship between Israel and the Palestinian Territories is characterized not by underdevelopment but de-development. The dominant party (Israel) is not only disrupting the economy of the dominated party (Palestine), but wholly undermining it. Furthermore Israel is undermining the Palestinians’ productive capacity to implement a rationally structured transformation or meaningful reforms.

Palestine’s economy continues to struggle as a result of the failure to form a unified government for the West Bank and Gaza in combination with Israeli restrictions on trade, movement and access. Weak investor confidence has been exacerbated by a significant decline in foreign aid.

Despite the growth of Gaza’s economy by 7.3 per cent in 2016, particularly in the construction sector following the 2014 war with Israel, Gaza’s gross domestic product (GDP) will not return to pre-war levels until 2018. The restrictions imposed by Israel are continuing to hamper the private sector investments that could stimulate sustainable growth, according to the World Bank.

GDP in 2015 was $12.68 billion, compared with $12.72 billion in 2014 and $12.48 billion in 2013. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts that GDP will grow by 3.5 per cent in 2017, compared with 3.3 per cent in 2016 and 3.5 per cent in 2015. Inflation is low, at 1.2 per cent, in part due to the drop in global fuel and food prices.

Overall, Palestine’s economic prospects are uncertain, according to the World Bank, given the likelihood of future conflicts and the decrease in donor support.