Introduction

Palestinian heritage will always remain the most important spring. It is the inexhaustible well for the various Palestinian literature and arts, for its significance affirming the Palestinian identity and embedding the Palestinians’ unity with all its religious and ethnic sects. Belonging to such heritage, supporting and reviving it, one generation after the other, is a holy cultural mission, around which all arts and literature are gathered, surpassing its spatial boundaries to the wider global spheres.

In this manner, the Palestinian heritage is one of the major indestructible resilience for the Palestinians in their journey of struggle that spanned for more than seven decades until today, towards retrieving their historical rights that was deprived of them by the Israeli occupation.

Since the middle of the 20th century or even before that, the culture of Palestinian lands was exposed to tireless attempts to obliterate its identity that is as eternal as its holy lands, as persistent as its ancient alleys. Nevertheless, the innovations of Palestinians – even those deceased – remain as resilient as a frim wall against these attempts.

Wherein the writings of Ghassan Kanafi are still inspiring a lot of intellectuals across the Arab world, let alone Palestine’s intellectuals. Poems of Mahmoud Darwish and Samih al-Qasim are also still echoing in official and public cultural gatherings. And the caricature character “Hanzala” of the famous cartoonist Naji al-Ali is still adorning the necks of young people of different ages.

Those and others have contributed to affirming the Palestinian heritage and reviving its aesthetics, in the context of forming the collective cultural awareness unifying the Palestinians.

Also, the bagpipe played with the Palestinian Dabke (a traditional group dance), alongside Oud and Qanun, are still some of the preserving means of the Palestinian culture, by clinging to its first melodies, which are plunged deep into Palestinian history.

In the fashion world, the distinctive hand-embroidered Palestinian dress sparkles with great craftsmanship, which can be found in every Palestinian house, In addition to men’s keffiyehs and Agal that are considered means of preserving the Palestinian culture alongside all forms of artistic and literary creativity.

Poster art is one of the arts Aesthetic and symbolic innovations that the Palestinians achieved, affirming their national beliefs through significant symbols like the Palestinian flag, the olive tree and Dome of the Rock, to promote values of belonging, faith, national unity and bonding with the land.

To learn more about the culture of Palestine and all its aspects, check what Fanack has covered about this file.

Palestinian Cultural Heritage

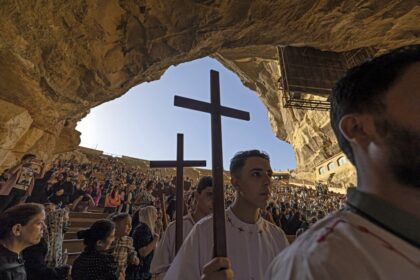

The archaeological history of Palestine is very rich, with approximately 12,000 sites in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. As home to three monotheistic faiths that consider the city of Jerusalem a holy city, Palestine is the site of many holy shrines and an unique architecture.

Palestine has been influenced by various cultures which left their mark on the region since prehistoric times. Its cultural heritage goes back to the 4th century CE, when in the Eastern Roman Empire ancient churches such as Burqin and Abud arose in the West Bank.

The Umayyad period (661-750) brought early examples of Islamic architecture. This period heavily influenced the entire Levant region in terms of its political and tribal powers’ luxurious standard of living. This standard is to be found in the designs of complex palaces containing auditories, baths, mosques, courtyards, and gardens.

During the Mamluk period (1250-1517) various types of buildings, especially religious institutions, left their mark on the Palestinian architectural landscape. The holy city of Jerusalem flourished, with madrassas (Islamic schools) and zawiyas (buildings especially for Sufis, the mystic school of Islam) being promoted. Public facilities, such as khans (roadside inns where travellers could eat and rest), souks (markets), and hammams (baths), were also part of the urban planning of the city.

Under Ottoman rule (1517-1917) a significant human settlement took place in the region, as more villages emerged influenced by Ottoman culture. After the fall of the Ottoman empire and the establishment of the British Mandate to Palestine, a department of antiquities was established in the 1920s to implement excavations and archaeological surveys. In 1929, the British government enforced the Antiquities Law; most of the work was done by British specialists as Palestinians did not possess the required skills for research.

After the collapse of Palestinian society in 1948 and the establishment of the State of Israel, Palestinians saw a full-scale destruction of their cultural heritage in the aftermath of the Arab-Israeli wars. Israel’s attempts to acquire a political, historical and cultural legitimacy in Palestine resulted in the exploitation, destruction and manipulation of the Palestinian cultural heritage.

Under Israeli occupation, Palestinians were prevented from carrying out local excavations, and archaeological evidence from periods succeeding those of interest to the Israelis – classical, Byzantine, Islamic – was often neglected. Hundreds of archaeological sites have been looted and plundered during the years of occupation, and there has been an active illegal trade in cultural property.

In the 1970s, a national interest in re-affirming ‘Palestinian national identity’ was rekindled and Palestinians began to safeguard what remained of the local heritage: i.e. historical buildings, monuments, archaeological sites, artefacts and art objects. Following the Palestinian-Israeli agreement in 1993, the Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities was created, which sought to invigorate research. The Department of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage (DACH) was established under complex circumstances. Despite its lack of archaeological records and inadequate logistical support and equipment, the department sought to preserve some of the most endangered archaeological sites and historic buildings.

Preservation and conservation of Palestinian cultural heritage

The Palestinian Department of Archaeology, with international collaboration and funding, was able to carry out a number of major projects. The Emergency Clearance Campaign of one Hundred Sites, in 1996-1998, and a project for the protection of the cultural and historical landscape between 1998 and 2001 included major archaeological sites and historical buildings, as well as mosques, churches, monasteries and sanctuaries, such as the ancient churches of Burqin and Abud, as mentioned both dating to the Byzantine period, and the crusader churches of Sebastya and al-Birah. Historic mosques likewise preserved include al-Sabeen and Burham from the Mamluk period, the Omari mosques at Dura and Birzeit, as well as the sanctuaries of al-Qatrawani and Maqam al-Nuban.

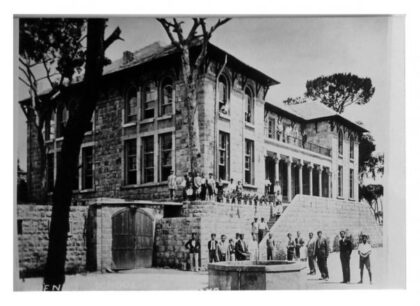

Illustrative of the diversity of structures and sites that have been preserved are an 18th century castle in Ras-Karkar, the crusader Kahn in al-Birah, the Mamluk bath in the old town of al-Khalil (Hebron), the Ottoman Qaem-Maqam house in Tulkarem and the Beit al-Zarru villa in Ramallah. Maqam al-Qatrawani near Attara has also been conserved, together with the small natural forest and terraced landscape surrounding it.

Similarly, the site of Dura al-Qarei provides a combination of historical ecology and technology, displaying traditional hydrological features in its natural and cultural landscape. Some historical buildings have been restored as ethnographic and archaeological museums or other types of cultural centres. The villages of Deir Istyia and Artas are being incorporated into larger complexes with multiple functions.

Among well-known sites excavated in the 20th century in the West Bank and Gaza are Tell Taannek (tell means ‘hill’ in Arabic), Tell al-Fara, Tell Dothan, Tell Balata, Tell al-Nasbeh, Tell al-Tell, Khan Radana, and Tell al-Ajjul (a Palestinian-Swedish excavation), which arose just before the foundation of Gaza City.

Excellent examples of the efficiency of international collaboration with the department are the joint Palestinian-Dutch excavations at Khan Balama, the joint Palestinian-Italian excavations at Tell al-Sultan in Jericho, the Palestinian-Swedish excavation at Tell al-Ajjul, the Palestinian-French excavation at Anthedon, Tell al-Sakan and the Palestinian-Norwegian excavation at Tell al-Mafjer in Jericho.

These joint projects have contributed to building a new postcolonial model of cooperation in archaeology based on mutual respect and interest, although some of the sites have been left unprotected during the thirty years of occupation.

In Gaza, Qaser al-Basha has undergone comprehensive restoration work. Major excavations also took place at Tell Umm Amer, Blakhyieh, Jabalia, and Tell al-Sakan between 1995-2006. The excavations at Tell al-Sakan are on-going despite the present difficulties.

It is a major Palestinian site for the third millennium BCE, whose exploration will reveal the ancient history of the Gaza Strip. As the UNDP states, ‘Discovered by chance in 1998 during the construction of a housing complex, it is the only Early Bronze Age site presently known in the Gaza Strip. Inhabited between ca. 3300 and 2200 BCE, this settlement of more than 5 hectares was possibly the capital of the area at the time.’

The Mamluk castle of Khan Yunis underwent a series of restorations and consolidation work in 2005. In the northern districts in Palestine, the sites of Khan Balama, Burqin, Arraba, Deir Istyia, Barqawi Castle are also being restored. For the People of Shofeh, the Barqawi castle is more than just an impressive piece of architecture, it is a central element in their town’s identity and local mythology.

UNESCO and Palestine

Since October 2000, cultural sites in the Palestinian areas have suffered extensive damage. These sites have been subject to military bombings and shelling leading to partial or even total destruction. Attacks on cultural heritage sites have intensified since the last major incursions in April 2002 and January 2004, causing irreparable damage, especially in the historic towns and cities, including Bethlehem, al-Khalil (Hebron), Gaza, Beit Jala, Tulkarem, Salfit, Jenin, Gaza, Rafah, Abud, and Nablus.

Many archaeological sites and historical buildings have been the target of Israeli military attacks, including during the last war on Gaza, when the ancient Gaza port of Anthedon, the Ottoman building of Dar al-Sariai and the governor’s house were damaged. Sieges, curfews, roadblocks and military closures imposed on the Palestinian cities and villages have prevented the DACH from attending to its tasks in the protection of the cultural heritage.

UNESCO weighed in when it affirmed that the ‘Palestinian sites are cultural treasures that the Palestinian people wish to protect and share with the world’. Condemning Israel’s annexation of Rachel’s and Joseph’s tombs, and affirming Palestinian sovereignty over them, UNESCO proclaimed, ‘the Israeli Government has attempted to highlight the Jewish character [of these sites], while erasing or neglecting the universal character of these heritage sites’.

This cultural hegemony, according to UNESCO, has been used ‘as a political tool to maintain and entrench control over Palestinian lands and as a pretext for its continued settlement activity’. Again in this instance, UNESCO appealed to Israel to recognize its commitments as an occupying power and to recognize that ‘confiscation and developments of Palestinian heritage sites and cultural property by Israel is prohibited under customary international law’.

Palestinians are seeking protection for their endangered cultural heritage, along with their membership of UNESCO since 2011. In the framework of the UNESCO World Heritage Centre’s contribution to the protection of Palestinian heritage, an international workshop was held in Jericho in February 2005, aiming at discussing strategies to preserve the outstanding universal value of Tell al-Sultan (Ancient Jericho), the oldest known city in the World. Palestinians also seek World Heritage Status for up to twenty sites.

Palestine’s folk heritage

Palestine’s folk heritage, including craft-making, oral traditions, and music, is part of the national wealth. However, many factors threaten the survival and continuity of the cultural heritage in Palestine, such as Israeli military occupation and the lack of awareness of the importance of cultural heritage among the public.

Literature and Art

Language has always been at the centre of Arab culture. Expressive Arab poetry is well-represented, as are satire and invective. Poems were sometimes sung by itinerant professional singers. To modern Palestinian poets (and writers), the Nakba has served as an inexhaustible source of inspiration.

Poets

The most famous Palestinian poet is Mahmud Darwish (1942-2008). His poems became widely known through the musical adaptations and recitals by the talented Lebanese singer, composer, and ud (lute) player Marcel Khalifé. Darwish has been dubbed the ‘Poet of the Arab World’, and once recited his poems in front of an audience of 25,000 people in Beirut.

According to the Palestinian sociologist, Samih Farsoun, Darwish’s poetry is a metaphor for the loss of earthly paradise, birth, death, and resurrection, and the fear of disinheritance, destitution, and banishment. Palestine is the earthly paradise twice lost. In his poems, Darwish also expresses sharp criticism of the Arab leaders who repressed the Palestinians or left them to fend for themselves.

Writers

Besides major poets, Palestine has also produced important literary authors and essayists, often originating from the well-to-do middle classes and including women. An important position is held by Ghassan Kanafani (1936-1972) among the modern writers. He too was a refugee in 1948, and started out as a painter. He combined his politically engaged authorship with a career as a journalist. In later years, he was also spokesman for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) in Beirut. On 9 July 1972, he was killed by a car bomb attack in Beirut. The general opinion is that the Israeli secret police were responsible for his assassination.

Violence against artists

He is not the only Palestinian artist to have met a violent death. The famous cartoonist Naji al-Ali (1938-1987) suffered the same fate. In his cartoons, appearing in leading Arab newspapers, he frequently exposed the political vacillations of Palestinian and other Arab leaders. On 22 August 1987, he was shot at in the streets of London and was severely injured, succumbing to his wounds a week later. The perpetrator was never caught, but was presumed to belong to Arab circles.

Iconic art

Up to the 20th century, painting was dominated by iconic art. This was of course related to the presence of the Greek Orthodox and later Russian Orthodox Church in Palestine and their close ties to the mother churches in Greece and Russia. In addition to Madonna with child, and scenes from Jesus of Nazareth’s Way of the Cross, the Saint George/al-Khidr (or al-Khadr) the Dragon Slayer was also a popular theme.

Influenced by western artists who were discovering the ‘Orient’ in the second half of the 19th century, Palestinian artists started to choose new subjects and adapt their method of working (such as painting and drawing in the open instead of in a studio). Various styles arose from this development, which to a certain extent bore resemblance to western styles of painting but nonetheless had a specific local character.

The Nakba also strongly influenced the art of painting. In this light, it is noteworthy that Palestinian artists in Israel, Palestine and neighbouring Arab countries predominantly produced figurative work depicting this and other dramatic events, whereas their colleagues elsewhere in the world mainly produced abstract works on the subject.

Performing Arts and Music

The performing arts, such as theatre and dance, have also been strongly influenced by the Nakba. The representation of the farming community as the bearer of the Palestinian identity takes an important place as a result of the ongoing struggle for possession of land. Exile is another, frequently recurring theme.

The dabke or dabka, a traditional group dance, is spectacular. In Arabic, dabka means ‘to stamp one’s feet’, which more or less sums up the essence of the dance. Its effervescent character is heightened by the accompanying music. Men and women both perform the dance. The dance originates from earlier times, when the rooftops of houses were made from wooden beams covered with a mixture of straw and loam which had to be stamped down. This was done in groups (as is so often the case in rural communities), and was often accompanied by singing.

Music

Some of the musical instruments which are used among others in the dabke performances are the ud, a stringed instrument with a pear shaped wooden sound box, the darbuka, a bowl shaped drum, and the ney, a plain flute. Another important musical instrument is the qanun, a stringed instrument with a flat sound box, in the form of a small harp, which is strummed in a horizontal position. These instruments are known to have been present in the Bilad al-Sham (and in its wide vicinity) for thousands of years.

In a city such as Ramallah, there is a reasonably well-developed cultural infrastructure: there are three large cultural centres – the Kasaba Theatre and Cinema, the Khalil Sakakini Cultural Centre and the Cultural Palace of Ramallah. The Cultural Palace is a large and well equipped theatre located on Tokyo Street – a gesture towards the government of Japan, which financed the construction and design. In addition, there are a few music schools and an academy of music.

This Week in Palestine is a useful magazine offering a monthly overview of the cultural activities in Palestine, besides interesting information about art and culture.

Dress

The traditional dress of men in Palestine and elsewhere in the Bilad al-Sham is the jalabiya, a loose-fitting cotton garment reaching from the shoulders to the ankles. In the evenings and during the autumn and winter, a woollen mantle, the abaya, is worn on top. The head is covered with a turban, made of a long strip of cotton cloth. The higher the social position, the higher the turban.

Bedouin men traditionally cover their heads with a keffiyeh or kufiya, a square piece of cotton. This was folded diagonally and then coiled around the head to protect the face from the sun and gusting desert sand winds. The keffiyeh is either white, or black and white checkered, and is held in place by a tightly knotted black band, the agal, when it is worn on the head.

In the course of the 20th century, the keffiyeh and the agal became the symbol of Palestinian nationalism, with non-Bedouins also starting to wear them. It was the trademark of the late Yasser Arafat.

Other Fashions

During the Ottoman Turkish Empire, the urban elite replaced the turban with the tarbush, a red felt hat in the form of a flower pot, topped by a black tassel. Western dress fashions also started to be adopted, resulting in mixed styles, such as wearing a jacket over the jalabiya (which can still be viewed in rural areas and in the cities).

During the British Mandate, western fashion became more influential. Today, men in both the cities and in rural areas predominantly wear western clothes. This especially applies to young men. However, the ‘re-Islamization’ of society has started to change dress styles once again.

Embroidery

In rural areas, women’s dress is traditionally richly adorned with embroidery. There can be differences per region or even per village. The basic cloth is coloured black or white. The embroidery is made up of threaded cross-stitches, the colours varying per region: red (Ramallah), ochre (Hebron), lilac (Gaza) and blue (Sinai).

However, the geometric embroidery motifs display large variations: the palm tree leaf (Ramallah), the cypress in various styles (Ramallah, Jaffa, Hebron), a pendant (Gaza), an amulet (Jaffa), or the ‘pasha’s tent’ (Hebron). Recently married women wear bright colours, widows in mourning dark colours. Embroidery is a living art, subject to changes in motifs and use of colours.

Embroidery is a skill which was passed down from mother to daughter. With the rise of Palestinian nationalism, the production of traditional Palestinian clothing migrated from the rural areas to the cities. Far away from home, in the refugee camps outside of Palestine, women continue to uphold this traditional skill, meticulously using the same colour and embroidery motifs of their region of origin.

Today, the older women still wear traditional embroidered dresses in everyday life. Young women, however, generally regard them as party dresses. In homes, numerous items such as cushions, address books, and tissue boxes are also adorned with embroidered covers. The tables are covered with embroidered cloths and framed examples of fine embroidery sometimes hang on the walls. Christians often depict Biblical scenes in their embroidery.

In the past decades, numerous centres have been founded in Palestine and the refugee camps dedicated to preserving the art of embroidery. Nationalist motives especially played a role here since these centres assist in the preservation of the Palestinian identity in dire circumstances. Moreover, the production of embroidery has become a source of income for women whose husbands are unemployed or in prison.

In contrast to Christians, Muslim women wear a hijab (headscarf) or a large veil outdoors or in the presence of those other than their direct family. This applies especially to women in rural areas and women who have migrated from rural areas to the cities. Many women wear a dress (jilbab) reaching from the shoulders to the ankles, sometimes topped with a vest or jacket. It is uncommon for women to wear the niqab (veil) in the streets (although Bedouin women do wear a veil). Young females, however, usually wear western clothing. But again, changes are occurring in the light of the ‘re-Islamization’ of society.

Sports

Games inherited from the Ottoman era were the starting point of Palestinian sports during the British Mandate. These games included horse racing, running, wrestling and swimming. However, football gained popularity over time.

The Palestinian national football team represents the country worldwide. The team scored its biggest victory of 11-0 against Guam at the Asian Challenge Cup in Bangladesh in 2006. The team ranked 94 internationally after winning the 2014 AFC Challenge Cup. The historic scorer of the national team, Fahd Atal, has scored 16 goals. For his part, Abdullatif al-Badhari represented the national team with the highest number of international matches (71 matches). In October 2020, Palestinian’s national football team ranked 104 in FIFA’s world ranking table.

Since 2013, the Palestine Marathon has been organized on the streets of Bethlehem. The goal of the marathon is to inform the world about what the Palestinians are going through and their restricted freedom of movement due to the Israeli pressure exerted on Palestinian territories.

Latest Articles

Below are the latest articles by acclaimed journalists and academics concerning the topic ‘Culture’ and ‘Palestine’. These articles are posted in this country file or elsewhere on our website: