Introduction

The historical evolution of Palestine‘s boundaries must be seen within the scope of the whole Levantine region. For most of its history, Palestine was a province of what is known as Greater Syria. Only for a few centuries was Palestine made up of larger separate kingdoms; throughout most of history, however, it constituted a provincial region of historical Syria.

Only in recent times was Greater Syria divided territorially into four separate states, largely as a result of Western geopolitical interests. These states are today’s Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Israel. The State of Israel was established on Palestinian soil in 1948.

Syria itself was reduced to a core area, covering less than 60 percent of its original territory; Palestine retained a third of its former territory. Palestine would undergo further dismemberment in 1948, when three-quarters of the remaining territory fell under the control of the newly established State of Israel.

Palestine in the Levant

Palestine‘s boundaries have been largely determined by the topography of the mountains and valleys in between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Desert. Its boundaries stretch in length from north to south, covering a narrower strip of land from west to east.

The elongated rift valley of the Jordan River running from north to south in between two parallel mountain chains forms the country’s structural spine. It is indented on both sides by numerous smaller valleys (wadis), descending to the west and the east.

In some places, these wadis become larger and wider, forming larger valleys that cut across the mountain chains. These are the principal terrain levels of mountains and valleys where natural boundaries could easily be turned into territorial, administrative boundaries.

Syrian Palestine

The Levant has known strong cultural and linguistic ties throughout its long history. It is known as Canaan and Syria, in reference to its cultural or geographical identity, respectively.

The Levant has known strong cultural and linguistic ties throughout its long history. It is known as Canaan and Syria, in reference to its cultural or geographical identity, respectively.

After it was absorbed into the Arabic Islamic commonwealth, the Syrian Levant became known as Bilad al-Sham, which carries the notion of ‘The North’ or ‘The Left,’ as seen from the perspective of the Arabian city of Mecca.

Until the 19th century, al-Sham or Syria stood for the whole settled area between the Mediterranean Sea and the desert, from the Gulf of Alexandretta (Iskenderun) in the north to the Gulf of Aqaba in the south.

Its centre was the city of Damascus, popularly known by the name of the whole region – al-Sham –, which served as the gateway to all provincial regions and countries farther away. Despite its cultural ties, Syria was also exposed to strong dividing forces, mainly in the spheres of religion and politics.

Most ancient Bronze Age city-kingdoms became absorbed into larger regional kingdoms in the period of the Iron Age. Syria was divided into a northern and a southern area, with the Lebanese mountains and the region of Damascus in the middle.

These areas were again divided into a western part along the coast that was characterized by mercantile cities and an eastern part of less populous rural regions in the mountainous interior.

The Romans

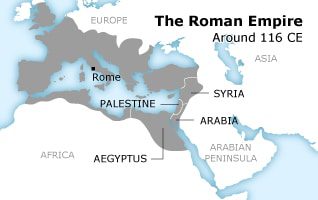

The southern area became known under different names depending on the viewpoint. The urbanized coastal area came to be known as Palestine. This designation usually took precedence over the names of the rural interior regions.

The southern area became known under different names depending on the viewpoint. The urbanized coastal area came to be known as Palestine. This designation usually took precedence over the names of the rural interior regions.

However, in periods when such regions exercised considerable power, their names could designate the whole region. This clearly occurred in the Hellenistic era, when the priestly kingdom of Judea took control over most of Syrian Palestine, lending its name to the province that the Romans created when they incorporated the kingdom into the empire.

After the Judean revolt of 70 CE was crushed, the province was renamed by the Romans after the coastal area of Palestine. It covered all of southern Syria, from the coast to the Eastern Desert.

Palestine in the Arab Empire

The Arabian caliphs who succeeded the Roman-Byzantine rulers largely upheld the empire’s provincial boundaries, merely adding an administrative unit called al-Urdunn (Jordan) to the north-east of Palestine.

When the Caliphate fell apart in medieval times, the Syrian coast was conquered by Frankish knights from the West, who created a number of crusader principalities, of which the Kingdom of Jerusalem was the most prominent; it stretched across parts of Palestine.

New Islamic dynasties, usually of Turkish origin, known as the Mamluks, managed to drive the crusaders out in the 13th century and to unite Syria with Egypt. They introduced a new, more intricate system of provincial administration.

It was made up of larger provincial governorates, named after regional administrative capitals. Palestine became divided in the coastal governorates of Gaza and Safed, with the hilly interior being assigned to the larger governorate of Damascus.

In the 16th century, the Sultanate of the Ottoman Turks gained regional hegemony and expanded its realm over most of the Arab world. The new dynasty left the existing system of provinces (vilayets or wilayat) more or less intact.

These were further divided into districts (sanjaks) and sub-districts (qadas). The southern part of Syria became the Eyalet of Damascus, incorporating all of historical Palestine on both sides of the Jordan River, with Jerusalem, Nablus, Acre and Gaza as important sanjaks.

The Disintegration of Syria

In the 19th century, Ottoman Turkey, viewed as ‘the sick man of Europe’, began to lose ground to Great Britain, France and Russia in areas of strategic importance. Its Syrian and Mesopotamian provinces positioned along major routes to Africa and the Far East became primary targets of Western geopolitical intervention. Both regions were demographically dominated by religious minorities whose conflicts prompted Turkish measures that were often decried as repressive in the West.

As a result, in the 19th century Ottoman Turkey separated coastal areas from the Syrian core province of Damascus in order to exercise closer control and placate European powers.

This resulted in a separate Vilayet (or Wilaya) of Beirut and in the separate Sanjak of Jerusalem and the Sanjak of Mount Lebanon, that from then on were directly governed from Istanbul. Both sanjaks were granted special religious communitarian rights, which amounted to autonomy for Mount Lebanon.

As a result, Palestine was split up into a northern part under the Vilayet of Beirut, a middle part administered as the Sanjak of Jerusalem and an eastern part across the Jordan River which remained part of the original province of Damascus.

The Sykes-Picot Agreement

World War I, in which Ottoman Turkey sided with imperial Germany and Austria-Hungary against Great Britain, France and Russia, would result in the dramatic disintegration of Syria. The war had galvanized Arab nationalists in supporting a British advance from Egypt against Turkish positions in exchange for the promise of Syrian-Arab independence.

World War I, in which Ottoman Turkey sided with imperial Germany and Austria-Hungary against Great Britain, France and Russia, would result in the dramatic disintegration of Syria. The war had galvanized Arab nationalists in supporting a British advance from Egypt against Turkish positions in exchange for the promise of Syrian-Arab independence.

However, Great Britain and France secretly conspired to divide and rule Arabia directly or indirectly. The so-called Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 projected a line running through northern Arabia to separate British and French zones of influence.

In addition, and unknown to Arab nationalists, Great Britain had expressed support for ‘a national home in Palestine for the Jewish people’ in the Balfour Declaration.The course of the Sykes-Picot line would be strongly influenced by rivalry among the European powers to the detriment of native populations.

Not only did the line cut right through historic Syria, it also deprived those communities of resources and infrastructure which ended up on the disadvantageous side of the line. British domination ensured an upper hand in drawing a favourable borderline at the expense of French interests.

In consultation with Zionist leaders Great Britain managed to impose a boundary that incorporated crucial water winning areas within its domain to the detriment of traditional Syrian and Lebanese rights.

All vital headwaters of the upper Jordan River in the Lebanese sub-district of Marjeyoun were apportioned to British Palestine, as was Lake Tiberias, so that Syrian fishing villages were separated from the boundary by a strip of just 10 metres.

France and Great Britain then resorted to compartmentalizing their areas of influence into separate states guided by the principle of divide and rule. For Palestine it meant that, due to the activities of Prince (Emir), later King (Malik) Abdullah, the area east of the Jordan River was severed from the western core and turned into the Emirate of Transjordan.

The border between the two was drawn in a similar fashion as Syria’s, offering British Palestine increased control over the downstream section of the Yarmouk River before joining the Jordan River south of Lake Tiberias.

The State of Israel

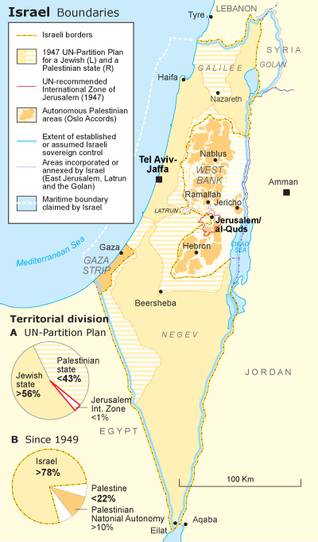

The imposed borderlines had reduced historical Palestine to about half of its original size. A further dramatic reduction would occur in consequence of the recommendation of the United Nations in 1947 to partition Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. British termination of its governmental mandate over Palestine in May 1948 was followed by the proclamation of the State of Israel.

After several rounds of hostilities between Israel and Arab armed forces an armistice agreement was enforced which produced the so-called Armistice Lines of 1949. It reduced Arab held Palestine to a mere 22 percent of its initial size, less than half the allotted territory according to the UN Partition Plan.

These lines separated Israel from the territories of Arab neighbouring states, two of which had taken control of the Palestinian areas not conquered by Israel: the Gaza Strip in the west which was administered by Egypt, and what became known as the (Jordan River’s) West Bank, that was annexed by the Hashemite kingdom of Jordan.

The absence of peace between Israel and its Arab neighbours meant that the Armistice Lines of 1949 replaced the international boundaries established by Great Britain and France after the World War I. The western boundary with Egypt dates from 1906, the northern boundary with Syria and Lebanon from 1923 and the eastern boundary with Jordan from 1920.

Apart from the Palestinian territories, the Armistice Lines of 1949 closely followed the course of the earlier established international boundaries, except in the north where Syria had managed to hold ground against Israeli forces in a number of places, restoring traditional access to the upper Jordan and Yarmouk Rivers and the north-eastern section of Lake Tiberias.

The ceasefire agreement between Israel and Syria stipulated a number of demilitarized zones that became hotly contested when Israel attempted to gain hold of them. Skirmishes over these areas soon escalated into violent exchanges over areas of the Jordan’s and Yarmouk’s headwaters emptying in Lake Tiberias which Israel turned into its exclusive strategic water reserve to irrigate the northern Negev, while bombing Syrian and Jordanian dams and channels which were being built to safeguard their respective shares of these waters. The violent incidents only ended when the whole region became engulfed in the June War of 1967.

The June War of 1967

The June War of 1967 resulted in Israel’s conquest of the Jordan West Bank (which Jordan had conquered in the Arab-Israeli War of 1948-1949), the Gaza Strip (which was conquered by Egypt in 1948-1949), the Egyptian Sinai and the Syrian Golan Heights.

The June War of 1967 resulted in Israel’s conquest of the Jordan West Bank (which Jordan had conquered in the Arab-Israeli War of 1948-1949), the Gaza Strip (which was conquered by Egypt in 1948-1949), the Egyptian Sinai and the Syrian Golan Heights.

The Armistice Lines of 1949 were replaced by a new set of lines attached to the ceasefire agreements of 1967. These lines ran along the Suez Canal in the west, the Jordan River in the east and the Golan Heights in the north.

At the beginning of the 1980s, Israel handed back the Sinai in exchange for a peace treaty with Egypt. It was Israel’s first legally recognized boundary with one of its neighbour states.

Shortly thereafter Israel annexed the city and surroundings of East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights. Both annexations were condemned and declared null and void by the international community.

Troubles ensued in the north and escalated when Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982 and occupied its southern part until 2000, when armed resistance of the Hezbollah movement, rooted in the local Shiite population, forced Israel to withdraw, although not completely.

Israel continues to occupy the village of Ghajar and the adjacent so-called Shebaa Farms, which are claimed by Lebanon. The exact demarcation of the northern border remains unresolved as a result of the Lebanese claims and is a source of tension, which eventually led to an all-out war in the summer of 2006.

In the wake of the Gulf War and the ensuing so-called Madrid talks, conditions were in favour of a resolution of the outstanding territorial differences with Jordan, facilitated by the earlier (July 1988) decision of the Jordanian monarchy to forsake all its claims to the West Bank.

The two countries signed a peace treaty in 1994 (see also The Oslo Accords in Arab-Israeli Negotiations). The only border conflicts still remaining are with Lebanon, Syria and the Israeli Occupied Palestinian Territories

Territorial Expansion

The Oslo Agreement of 1993 between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) stipulated negotiations between both sides with the aim to arrive at an agreed permanent status of the Occupied Palestinian Territories, pending a solution for such issues as Jerusalem, the Jewish settlements, water, security, refugees, and borders.

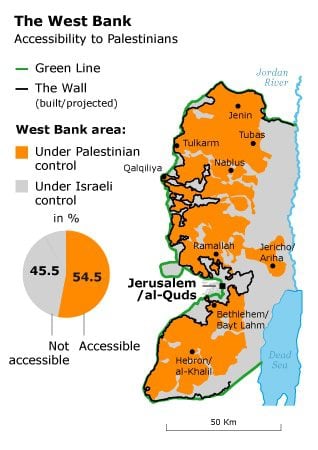

Since conquering the West Bank and Gaza Strip in 1967, Israel has shown no regard for the Palestinian side of the equation. To the contrary, taking guidance from the so-called Allon Plan, Israel defined its geopolitical security in such a way that Palestinian geographic cohesion would be effectively dissolved.

In the first place, this was achieved by isolating Palestinians in the West Bank from the large Palestinian refugee community in Jordan by means of a string of settlements in the Jordan Valley.

Secondly, this was done by encapsulating East Jerusalem by means of a belt of settlements around the city. Thirdly, Israel opened the West Bank’s interior to settlement by Jews, aiming to fragment areas populated by Palestinians.

Israel’s construction of what is called the Separation Barrier (hereafter the Wall), which began in 2002, signalled a new course with regards to the initial Allon Plan. Officially justified as a necessity to prevent Palestinian suicide bombings, the Wall’s actual course across the West Bank indicates additional territorial objectives.

Although primarily built within the West Bank, it only partly follows the so-called Green Line (the armistice line between Israel and the West Bank), and makes deep indents at various places that leave the largest settlements on the ‘Israeli side’ of the Wall.

Taking up some 7 percent of the West Bank’s area, the Wall incorporates more than 80 percent of the Jewish settlements, as well as a number of Palestinian villages and neighbourhoods in East Jerusalem.

Together with the closed off areas of the Jordan Valley, the Wall imposes a territorial configuration offering Israel all the benefits of the original Allon Plan and leaving the Palestinians in a disadvantaged position.

This has raised concerns within the international community whether the Wall can be considered compatible with the targeted two-state solution, which stipulates that Palestinian viability is equally important as Israeli security.

Dismantling Jewish Settlements in Gaza and the West Bank

Partly in response to international criticism, leading Israeli politicians aimed to balance construction of the the Wall with initiatives of withdrawal from the Occupied Palestinian Territories. It was Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, whose hawkish reputation carried much weight, who managed to muster enough internal support to initiate what was called ‘unilateral disengagement’.

Dismissing opportunities to reach an agreement with Palestinian leaders about the extent of Israeli withdrawal, Sharon advocated evacuating settlements from densely populated Palestinian areas deemed irrelevant within the overall scheme of the Allon Plan. In the summer of 2005, Israeli army units evacuated all Jewish settlements in the Gaza Strip and a small token number in the northern West Bank.

The removal of 8,500 Jewish settlers from 21 Jewish settlements in the Gaza Strip was completed in August 2005. Yet according to UNISPAL, Israel’s withdrawal of settlements and permanent military ground installations did not end Israeli control of Gaza, but rather changed the way in which such control is effectuated. Israel continues to control Gaza through:

- Complete control of Gaza’s airspace and territorial waters;

- Substantial control of Gaza’s land crossings;

- Control on the ground through incursions and sporadic ground troop presence (‘no-go zones’);

- Control of the Palestinian population registry (including who is a ‘resident’ of Gaza);

- Control of tax policy and transfer of tax revenues;

- Control of the ability of the Palestinian National Authority to exercise governmental functions; and of

- the West Bank, which together with Gaza constitutes a single territorial unit.

Under Pressure: Ehud Olmert

The policy of ‘unilateral disengagement’ lost momentum when Sharon suffered a massive stroke, necessitating his deputy Ehud Olmert to accept his responsibilities. Lacking the prestige of his predecessor, Olmert came under pressure from all possible fronts.

His government responded rashly to an armed operation by Hezbollah, initiating massive air attacks on Beirut and South Lebanon (summer 2006). Wreaking nothing but havoc and failing to defeat Hezbollah on the ground, Olmert’s political stature was undermined.

His downfall became inevitable when, in a repeat of the invasion of Lebanon, the Gaza Strip was invaded (December 2008-January 2009), which increased Israel’s political isolation.

Possibly influenced by his precarious position and as if to compensate for Israel’s belligerence, Olmert aimed to make diplomatic headway with a plan for a Palestinian State that would restore the territorial percentage of the areas occupied by Israel since 1967.

His plan, disclosed in 2008, envisaged incorporation within Israel of areas west of the Wall and around Jerusalem in exchange for equal areas of Israeli territory adjacent to the southern West Bank and the Gaza Strip. Although unprecedented in projecting territorial equitability for both sides, Olmert’s plan had serious defects in the eyes of the Palestinians.

Further Settlement Expansion: Benjamin Netanyahu

Olmert’s territorial exchange percentages might be equal, but the value of the lands was not. Israel would gain precious urban development plots in the country’s centre while the Occupied Palestinian Territories would obtain marginal lands in the country’s periphery that were lacking any potential for urgently needed urban development.

Olmert’s plan evaporated when he left office, to make place for his successor Benjamin Netanyahu who spoke of further settlement expansion instead of further Israeli withdrawal.

There is however evidence that Olmert’s plan has raised interest with American politicians who are growing impatient with what is increasingly seen as Israeli intransigence. This is viewed as a liability to Washington’s geopolitical objectives in the region.

There can be little doubt that in the US’ opinion, the Wall cannot be sustained as a definitive boundary between the two states. But the principle of equal land exchange within a margin of a couple of percentages appears to find favour in Washington and European capitals. It would require Israel to decrease the area taken up by the Wall and Palestinian leaders to accept a future Palestinian state of reduced dimensions.

Palestinians have, in their view, already displayed an attitude of far-reaching compromise. They have expressed readiness to give up more than half of the vitally important areas in and around East Jerusalem, in return for practically worthless wasteland far away.

Thus far, Israeli leaders have not seemed prepared for any further compromise except for a retreat behind the Wall, which is already viewed as a far-reaching measure within influential military and political circles.

Giving up the Jordan Valley would mean abandoning half of the territory according to the Allon Plan, retention of which is seen as instrumental in safeguarding Israel’s security.

Provisional Palestinian Boundaries

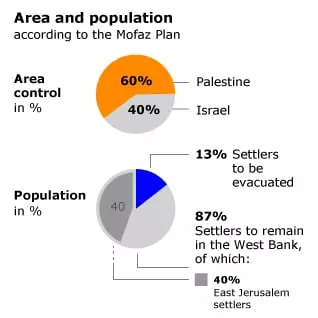

Without a breakthrough on the diplomatic horizon more attention is being paid to another interim solution that would answer the political objective of a Palestinian state within provisional boundaries, articulated in the Road Map of 2005, and in the 2009 Mofaz Plan, named after former Defence Minister Shaul Mofaz. All parties involved, including Israel, recognize the advantages of such a step, but are discouraged by the political price that has to be paid.

Without a breakthrough on the diplomatic horizon more attention is being paid to another interim solution that would answer the political objective of a Palestinian state within provisional boundaries, articulated in the Road Map of 2005, and in the 2009 Mofaz Plan, named after former Defence Minister Shaul Mofaz. All parties involved, including Israel, recognize the advantages of such a step, but are discouraged by the political price that has to be paid.

Palestinian leaders have announced that they are preparing for independent statehood by 2011, urging the as of yet fruitless negotiations to arrive at the targeted two-state solution. One thing is clear: the anticipated Palestinian state must have different and better boundaries than the current archipelago of territorial fragments shaped by the Oslo Process.

But there are signs that the road toward the two-state solution may proceed without reaching agreement on issues such as Jerusalem, the Jewish settlements, the Palestinian refugees, water and borders.

Whereas the Israeli redeployments of the Oslo Accords came in the form of dictates which gave the Palestinians little other choice than to sign them, unilateral disengagement, welcomed in Western capitals, could initiate further Israeli redeployments without the need for a Palestinian signature in order to enable functional, but limited Palestinian sovereignty in the West Bank in between the Wall and the Jordan Valley.

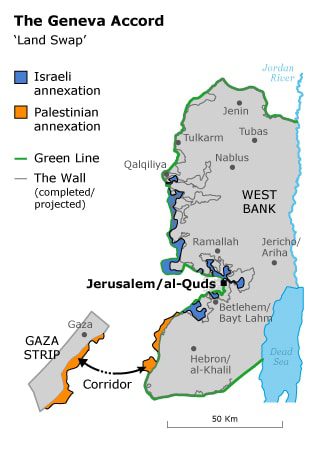

The Geneva Accord

One of the more influential plans put forward in peace negotiations is the Geneva Accord of 12 October 2003, drawn up by a former Israeli minister, Yossi Beilin, and a leading figure in the PLO/PNA, Yasser Abed Rabbo.

The main elements of the agreement were: the Palestinians would give up the Right of return, but would be free to settle in the newly formed Palestinian state; a Palestinian state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip on the basis of the 1967 border lines, with border modifications as a result of the annexation of the big settlement blocks (compensated by land that since 1948-1949 had been part of Israel); Jerusalem as the undivided capital of two states, but administratively divided into Jewish and Palestinian parts; and international protection for the Holy Places.